YEAR ONE OF THE ANTI-DEPORTATION STRUGGLE IN CHICAGO DURING TRUMP’S SECOND TERM by the LAKE EFFECT COLLECTIVE

On September 6th, President Donald Trump publicized an AI-generated image depicting himself as the fictitious Lt. Colonel Bill Kilgore of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 film Apocalypse Now. Kilgore, a genocidal maniac played by Robert Duvall, is best known for his love of surfing, his bombardment of Vietnamese villages set to the soundtrack of Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries,” and his ultimate declaration: “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.”

Recast in his image, Trump squats in U.S. Army greens, peering through aviator sunglasses tucked snugly beneath the same U.S. Cavalry Stetson hat worn not in Vietnam, but the Army’s genocidal wars against Native peoples in the nineteenth century. Above Trump’s head, a squadron of attack helicopters descends on the city of Chicago. Napalm tumbles from the sky, alongside the words, stylized in the manner of the film: “Chipocalypse Now.”

“I love the smell of deportations in the morning…” Trump’s accompanying post declared. “Chicago about to find out why it’s called the Department of WAR.”

What could the President of the United States mean by this? Could he have in mind what the image seemed to propose: that civilization and barbarism are one and the same in the form of settler colonialism, and that their perfect identity is just as evident in the Belgian Free State — the setting of the Conrad novel on which Apocalypse Now is based, where millions were massacred in service of rubber extraction — as it is in the genocide of Native peoples in the Americas, the Vietnam War, and the pending operation in Chicago? In more practical terms: what kind of operation did the President’s communiqué actually portend? When, and where, would federal agents strike first? Who would fight, and who had already capitulated? Above all, how do we separate truth from spectacle?

The ambiguity of these kinds of pronouncements makes Trump’s near absolute power seem like nothing short of fate. But in his rhetorical posturing, we glimpse the slow, face-saving waddle that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents adopt when they retreat from a conflict they don’t like the looks of. Neither the chief executive nor the state, nor any state, knows how to resolve the contradictions of a falling rate of profit, the shedding of living labor from production, the decline in standards of consumption in Western nations, the diminishing importance of the United States in the global capitalist market, the inevitable failure of crops and hollowed states alike, and the resulting migrations that push the fiction of national boundaries to their breaking point.

A population that strikes one fraction of the ruling class and its petty-bourgeois allies as being totally expendable is to another a desirable pool of exploitable labor. In many instances, resistance to ICE is a direct expression of these exact contradictions: suburban homeowners taking brave risks in defense of the people they pay to watch their children and do their yard work, tech companies and parts fabricators suing to keep skilled laborers from China and South Korea. Migrant laborers in California, who, when deported, are not necessarily replaced by laborers with citizenship, end up leaving produce to rot on the ground — driving up grocery prices, and, in turn, depressing the President’s approval ratings.

There is no reason to suspect that either the Republican party in its current configuration, or the next President, will find a way of resolving these contradictions; they will only continue, ineptly, to manage the nation’s decline. What’s left are cruel public relations campaigns targeting some of our society’s most powerless people.

Like Lt. Colonel Bill Kilgore, Trump knows how to stage a spectacle. But just as Kilgore hoped the massacre would be over in time for him to catch some waves, Trump has proven impatient that his federal invasions of major U.S. cities like Chicago have not played out as smoothly or decisively as his media mythology has promised. Instead, 2025 unfolded chaotically, contradictorily, irreducible to sound bites and Hollywood plot points, driven instead by the self-activity of countless anonymous participants.

As a small group operating on a massive stage, facing events that often outpaced our ability to recalibrate to them, we, like many others, have attempted to decipher the reality behind the bluster and chart a course forward in a moment where virtually anything can happen. The best way to do this is to proactively seek out useful interventions and search for potential allies, rather than waiting for a real emergency that would force everyone to act. The purpose of this writing, then, is to record our understanding of the last twelve months of anti-ICE and anti-Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) activity in Chicago.

The reflections that follow are based on our political experiences and first-hand knowledge. Omissions should be understood accordingly. Over the past twelve months, countless groups and individuals have stepped up and behaved with heroism and ingenuity, and we do not pretend to be telling their stories. If your year was different from what’s recounted below, you disagree with our conclusions, and you’re fighting for the same things we are, please don’t take offense. Consider writing your own version. And be sure to hit us up — let’s be friends!

Setting the Stage

In December of 2024, twenty-six Republican governors released a joint statement saying they would use local police and the National Guard to enforce Trump’s planned deportation crackdown. This suggested to us that his term would begin with a rapidly escalating conflict between Democrat-controlled state governments on one side and the federal government and Republican-controlled state governments on the other. While Trump’s efforts to cut federal funding to Chicago during his first term largely failed, getting revenge on Chicago and other sanctuary cities remained a clear priority.

For those in favor of a revolution in the United States, the question became how best to exploit conflicts between the federal and state governments for revolutionary ends, and win a burgeoning three-cornered fight between us, the layer of the state captured by the right, and the layer of the state retained by liberal Democrats. The terrain we prepared to fight on was fraught. Chicago’s famous political machine lives on in the deep ties between local Democrats and Alinskyite community groups, and, more recently, professional social movement non-profit organizations, all of whom are fiercely territorial and adept at icing autonomous actors out of street-level politics — even if these organizations aren’t very good at much else.

Working-class Chicago was also divided. Texas Governor Greg Abbott had already spent over two years busing asylum-seeking Venezuelans to Chicago, attempting to foment a political crisis around the city’s sanctuary status. The stunt succeeded in stretching the city’s resources thin, and more so in dividing Chicagoans on the question of migration — most notably, perhaps, on the South Side, where Venezuelans received little sympathy from Chicago’s virtually abandoned working-class Black communities. Trump’s 2024 appeal to Black voters that migrants were taking “Black Jobs” was widely ridiculed by liberals; it was far less humorous to those of us who had been paying attention to how salient this issue had become among Black Americans, many of whom had come to view these migrants as yet another group receiving preferential treatment from the racist establishment, at their own expense.

Meanwhile, the radical milieus we navigated, saddled with inherited sensibilities around escalation, symbolic activity, and repression, remained heavily fragmented and defined by mistrust towards others, verging on paranoia. It was necessary to break this cycle.

At this point in the year, it was unclear what shape the anti-ICE struggle would take. In 2017 and 2018, people crowded into airports to prevent deportation flights and erected blockades and encampments at ICE facilities across the country — what would make sense in 2025?

While the specific form of raids and detention was uncertain, a significant amount of regional ICE infrastructure was already in place, including processing centers, airports, offices, and courts used by ICE and Border Patrol. Illinois and Chicago’s Democratic Party governments were applauded for their nominal resistance to Trump’s deportation program, but this infrastructure had been allowed to operate largely unimpeded before the inauguration. Its geographic distribution and capacity for carrying out deportations would become crucial to the year’s struggles.

In December 2024 and January 2025, activists conducted teach-ins, distributed know-your-rights information, and disseminated information about ICE’s local infrastructure as widely as possible. Some logistical bottlenecks in ICE’s deportation machine became apparent. Given the small size of the state’s sole ICE processing center in Broadview, the absence of large-scale detention centers, and the state-level ban on ICE’s use of Chicago’s carceral infrastructure for immigration purposes, it seemed like ICE simply would not be able to meet their deportation quotas without either solving their numbers problem, building a new facility, or winning a protracted legal battle that could open up Cook County Jail for detentions.

This bet paid off for the first half of the year, as ICE activity fell into a fairly stable pattern: teams of three or four agents, from a variety of random agencies, would zip around the city from location to location, trying to meet their quotas despite their small numbers, prioritizing speed. They would arrive at a location, knock on the door, and hang around for a few minutes; if no one answered, they would move on to the next spot. Time and time again, rapid responders would scramble to respond to a tip, only to find no agents present.

While the response from Democrats and progressives was insufficient and symbolic, many of their legal maneuvers at the state, city, and individual case levels have, in fact, slowed down the feds. In particular, while state and local non-cooperation with ICE has surely not always been observed, detention and deportation are much easier in states where the cops and jail systems directly facilitate the deportation process. These laws did not appear overnight, nor are they simply the cynical maneuvering of city and state officials to appear more radical than they are. Instead, they were the product of concerted liberal activism by numerous non-profits. This includes groups like the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR), with whom we disagree about anti-deportation tactics, who nonetheless can furnish defensive victories in the political arenas they are more suited to operate within.

On the other hand, groups like ICIRR and Organized Communities Against Deportations (OCAD) had staked out post-deportation legal aid and service provision as their exclusive territory — as well as the sole territory of contestation. Any project attempting to disrupt or directly stop deportations by collective means faced enormous hostility from established organizations. As scores of third-party actors entered the fray in 2025, the ensuing conflict consumed a great deal of energy and time throughout most of 2025 to unclear ends.

Rather than wait for this division to run its course, some of us spent the early months of 2025 facilitating tech-based rapid response and disseminating information about ICE tactics, uniforms, vehicles, and infrastructure, to help others learn what to look for and where to go. A small January 2025 action at the Gary Airport, the site of many deportations from the Chicagoland area, represented a kind of dry run, testing the capacity of autonomous crews to descend on a critical piece of deportation infrastructure. Another, in March, tested whether we could bring the same type of action to Chicago itself.

For the first half of the year, people built local rapid response networks, primarily under the auspices of the major immigration nonprofits, and began to develop a sense of where demonstrators could most directly interfere with deportation operations. This produced a split between two burgeoning groups: one represented by Democratic Party-loyal activists, typically cooperating with or employed by major Chicago nonprofits, and people disaffected with or unconvinced by existing efforts on the other.

This division broke on the same murky lines as the one between escalation and negotiation during the Palestine movement, as the legal support-oriented nonprofits condemned and punished individuals who intervened in ongoing deportations, and unaffiliated people started from the ground floor to build the skills and connections necessary to intervene intelligently. The latter called themselves “autonomous” for most of the year to underscore their separation from the state, political parties, or major nonprofits. As the year progressed, this scattered group did its best to stay a step ahead of outmoded tactics and antiquated strategic concerns. To emphasize this maximalism — the practical content that enabled all of their ideological heterogeneity to hang together — we’ll call them “ultras.”

Dog Days

Resistance to the deportation machine remained primarily local and ad-hoc until the early summer, when scenes of militant mass confrontations in the streets of Los Angeles raised the specter of a contagious popular uprising. On Tuesday, June 10th, two solidarity demonstrations were called downtown. The Stalinist Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL), whose mass actions consist of large, heavily stage-managed parades, scheduled one in the early evening, in a large, unimportant plaza nearby. Another was called anonymously, earlier in the day, outside the immigration court at 55 E. Monroe St., where masked ICE agents had been making opportunistic detentions outside of courtrooms since May. Each of these began in the mid-afternoon with moderate attendance, but after 5 p.m., the crowd downtown swelled massively, presumably as word had spread among people who were just getting off work. By this point, the two demonstrations had merged, and the PSL had lost its ability to shepherd its audience. Consequently, the thousands who joined late in the afternoon formed autonomous marches, moving in various directions: some towards downtown ICE infrastructure, others to nowhere in particular.

In some ways, the scene was similar to the first days of 2020’s uprising: crowds were too large and in too many places to be effectively policed. But the crowds’ tactical decisions and priorities had more in common with the mid-2010s emphasis on highway blockades and civil disobedience: several breakaway marches turned themselves east towards the lake and immediately beelined for Lake Shore Drive, where the majority of the day’s participants walked on the highway and then turned and made their way back to the city. Crews that passed near infrastructure didn’t know what to do with their opportunity, and attempts to draw the crowd’s attention to ICE sites during the high point of the breakaways were unsuccessful. By the time a hard core of stragglers ended up at the federal field office later that night, they were smaller, weaker, and outmaneuvered by the police.

With this omission in mind, ultras decided to emphasize sites of physical ICE infrastructure downtown, including an immigration court, the field office, and a nearby check-in office. Alongside this specific effort came a broader push to produce pamphlets, flyers, and maps that identified accessible ICE infrastructure that formed bottlenecks in the region’s deportation routes.

In late May and into June, autonomous protesters gathered outside the entrances to the immigration court, located in a privately owned building at 55 Monroe. They blocked the doors to the building’s garage, first with their bodies and soon with overturned dumpsters, Divvy bikes, and other city debris. The management company of the high-rise was also targeted by a phone-zap campaign, apparently designed to wear out ICE’s welcome. Outside, disagreements arose over whether to blockade the site entirely and inconvenience everyone in the building, or whether to focus narrowly on ICE vehicles and let contractors in. This strategic difference lacked a proper outlet for discussion and was never satisfactorily addressed, allowing confusion to reign.

Meanwhile, the Chicago police, in a rare instance of compliance with state and local prohibitions against conducting enforcement operations with ICE, turned a blind eye. One cop asked a group of masked anarchists whether anyone would like to pretend to be in charge and talk to him, and walked away in exaggerated disappointment when no one responded. Despite these auspicious circumstances, or perhaps because of them, groups like OCAD, ICIRR, and the PSL refused to acknowledge the growing campaign around ICE infrastructure.

Nonetheless, word spread through alternative communication channels adjacent to autonomous direct-response networks. After a No Kings protest downtown, a breakaway march attempted to sit down in front of the immigration court building’s entrances and exits. Participants, predominantly young people politicized by the moment and unfamiliar with Chicago’s activist world, gestured to the intended target with flyers listing its location and significance, which had been distributed at the march. A speaker blared Vic Mensa’s “16 Shots,” but the mass had missed its opportunity to break a scattered bike line before a hundred more police officers showed up; stray demonstrators threw empty water bottles at the police as the crowd gradually dispersed from the plaza it’d been penned into.

After a week of harassment, minor sabotage, and attention from large crowds, building management at 55 Monroe restricted ICE’s access to its loading docks and service elevators, effectively ending the routine deportations from the court. While not successful in freeing already-detained immigrants or stopping detentions at the courts across Chicago’s far-flung suburbs, pressure on the building and the constant harrying of ICE put a stop to ICE kidnappings at this location. This was a small infrastructural, place-based victory: a chokepoint in the deportation machine was located and publicized by various groups, and people acting without direction from any political party or bureaucratic organization forced ICE to back away.

But the ad hoc nature of this blockade was also a weakness. The agglomeration that stopped deportations at 55 Monroe struggled to redirect its energy once individual deportations were no longer occurring at the site and, once more, disaggregated. While some wanted to stay at the court until the leasing agency dropped its contract with the federal government, this goal was not openly disseminated or debated, leaving the few thinly-stretched people on the ground to make individual judgment calls. Had participants openly stated what was discussed privately about the stakes and aims at 55 Monroe, the struggle there may have continued past the initial small victory; it might even have led to the cancellation of the contract and the closure of the court itself.

Without a clear objective to rally around, those on the ground chose to go to a much less easily disruptible, more heavily policed federal building at 101 W. Ida B. Wells Drive, similarly erased by the major nonprofits, to gather further information on the downtown infrastructure. From then on, the already dwindling numbers at 55 Monroe almost fully switched over to Ida, effectively closing the window of opportunity there for the remainder of the year. Unfortunately, unlike the central location for immigration court proceedings at 55 Monroe, only one or two courtrooms were active at Ida at a given time. And because it was housed in a federal building rather than a privately owned, multi-use building like 55 Monroe, surveillance and intimidation by CPD and DHS were far more intense.

In general, this made the site more difficult to popularize with people outside the worn-down contingent dedicated to demonstrating at every piece of Chicago ICE infrastructure; clearly defining an achievable goal at the location was harder still. This was, in no small part, due to lesser numbers and the fact that there was less ICE activity at the site in the first place. While the observation of vehicles coming out of the site proved useful for identifying potential activity in neighborhoods ahead of time, on-the-ground protesters struggled to do much more.

ICE Floods the Zone

In the final weeks of August, the Trump administration announced its intentions to send the National Guard and other military personnel to Chicago, under the pretext of addressing crime and homelessness. Predictions piled up: would they be used for terroristic shows of force in highly public spaces, like in LA? Were they intended to bolster a federal takeover, like in D.C.? But the National Guard never materialized, held up by battles in the courts and eventually declared illegal by the Supreme Court.

In the last days of August, DHS announced that the Great Lakes naval base in the far northern suburbs of Chicago would be used to host immigration enforcement operations. Online spectators around the country praised Mayor Brandon Johnson for allegedly blocking the city’s main arterials and highway entrances with salt trucks, after a 50501 Movement account posted a video of city salt trucks blocking roads during the Taste of Chicago festival, falsely claiming the trucks were positioned to block federal agents. Novelty t-shirts appeared with the message “Salt Melts ICE.” Few recognized it as a common crowd control tactic, which the city government has used at planned festivals, protests, and flashpoints of potential rioting since 2020.

As CBP trucks from the Southwest headed north, peaceful demonstrations organized by liberal organizations, nonprofits, and the PSL were held at the Naval Base and in downtown Chicago. That weekend, September 6th-7th, a surge of federal immigration enforcement swept the Southwest Side, abducting a sidewalk flower vendor, a person waiting at a bus stop, and a person walking on the sidewalk. And on Monday, September 8th, DHS officially announced “Operation Midway Blitz,” a deployment of federal agents for immigration enforcement, scheduled to last at least a month. It would last around two months before the main occupation force would be deployed to warmer cities during the Chicago winter.

Historically, CBP’s powers have often extended beyond their nominal hundred-mile jurisdiction. From 2005 to 2011, CBP’s Border Patrol Tactical Unit (BORTAC) was deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, and in 2020, it was deployed to Portland to kidnap people off the streets. During Trump’s 2024 campaign, he consistently claimed that “every town is a border town,” and in L.A. and Chicago, this settler colonial fever dream was put into practice. Due in part to ICE’s seeming inability to “get the job done,” Gregory Bovino, a Border Patrol agent, was placed in control of the domestic invasions in L.A. and Chicago, and from September on, the distinction between the two agencies essentially dissolved. At the end of October, Border Patrol fully replaced the leadership of ICE, and the cowboys were fully in charge.

The additional federal personnel were felt immediately in immigrant neighborhoods on the Southwest Side, Northwest Side, and throughout the suburbs. Through September, agents continued moving quickly in teams of two to four, snatching one person at a time. But unlike the first half of the year, they actually had the numbers to accomplish this effectively. And, through a combination of packing the cells at the Broadview processing center and constantly transferring abducted migrants to nearby carceral infrastructure in other states pending flights out of the Gary Airport, they were able to address, in part, their earlier infrastructural bottleneck. By all accounts, ICE had overwhelmed the city’s ability to resist effectively.

Atrophied rapid response groups struggled to intervene on the ground, and the territorial, backlogged, and Byzantine training and vetting process of the main ICE-sighting hotline run by ICIRR was swamped and slow to onboard new volunteers. Social media, WhatsApp, and Signal groups were inundated with information about sightings, with varying degrees of accuracy, as people struggled in flailing chats to re-establish information standards. While details of sightings shared online helped people understand which areas were being targeted and disseminate knowledge of typical vehicles, license plates, uniforms, or hotels where they were staying, these reports nearly always arrived too late or contained too few details to facilitate effective action. And, as in other cities, the roving teams of ICE and CBP seemed to be working on an even faster timeline than before, making it unlikely that more than a handful of people would ever interfere with an abduction.

Throughout this period, the feds seemed to cycle through the neighborhoods of Chicago in a consistent pattern; every day, agents would concentrate on the Southwest Side, while a neighborhood-cycling contingent of agents would pick a new side of the city each day, and later each week, going counterclockwise from the North Side to the South Side, then repeating.

Across the city, Chicagoans finally saw the surge they expected in January and jumped into the fray to resist, in many cases heroically. As in January, Chicagoans distributed know-your-rights information across the city in every space they could; now, they compiled lists of known ICE license plates, tracked vehicles in cars and on bikes, located hotels and organized overnight noise demos, tracked helicopters across the city, conducted trainings on how best to resist agents on the ground, and followed ICE vehicles with whistles and gear from site to site, warning others and bringing themselves along for whatever confrontations could follow.

The whistle became ubiquitous as a tool that all Chicagoans should have for warning their neighbors about ICE, finally de-prioritizing the hyperspecialized, tech-based rapid response that had previously been the de facto ground floor for mass participation in Chicago. And, fed up with being told they could not intervene in the abductions of their neighbors without first receiving official “training” and “vetting” from the extremely backlogged ICIRR, some organized their own rapid response and car patrols, in person and in hyperlocal Signal chats, with far fewer hangups about “intervention.” On the one hand, more people were resisting than ever before; on the other, people’s activity often got stuck in the same old rut of action for its own sake, with no clear strategic outlook.

At this point, it became clear to us that a citywide rapid response network was top-heavy and impractical. Local networks were best used for patrolling hotspots and staging areas, not responding to reports of kidnapping in progress. And above all, the single best deterrent against abductions was not a squadron of specially-trained intervention forces, but the spontaneous activity of great masses of unaffiliated people who witness ICE activity, and take bold and decisive action to impede it. For organizers, then, the M.O. became less about absorbing more people into formal projects and more about publicizing intervention tactics and tools, like the whistle, and spreading the word that they are effective.

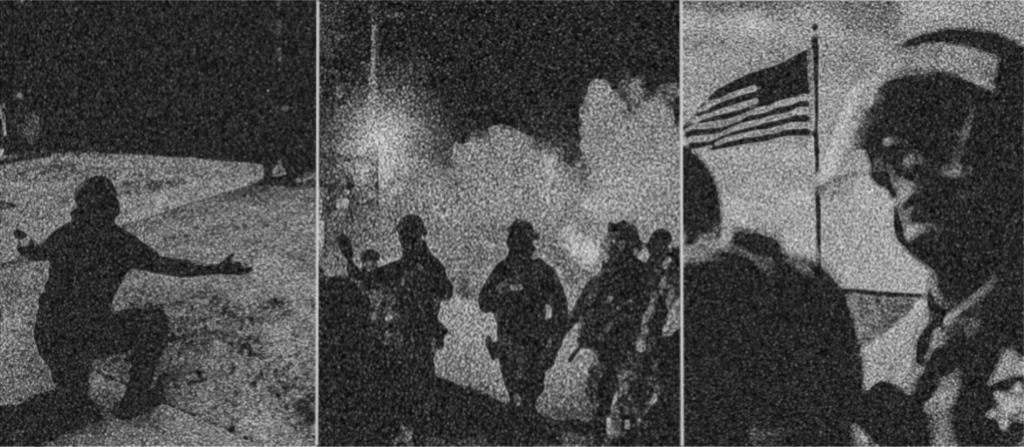

In early October, the feds started making liberal use of tear gas as they conducted their patrols around the city. As federal presence expanded and relied more on spectacular acts of force, with Bovino-led caravans of obvious ICE vehicles, it became much more common for large groups of people, including organized rapid responders, to tail their caravan. As Chicagoans, with whistles in hand, responded more spontaneously and actively, confrontations piled up. These frequently led to standoffs, either because a crowd of people in the area gathered to resist a kidnapping or because the feds made an extreme show of force, usually by creating a car crash.

On October 20th, during court depositions concerning use of force violations, an ICE official claimed that approximately three hundred agents were stationed in the six-state Chicago Area of Responsibility. Of these, eighty-five ICE agents were stationed near Chicago itself. While it is unknown how many of them had received crowd control training, demonstrators at Broadview experienced ICE’s behavior as extremely jumpy. This makes sense: compared to CBP agents, who could treat Midway Blitz functionally as a tour of duty, a larger proportion of ICE agents live in the area, and as a result, are less acclimated to CBP’s cowboy tactics and more fearful of social consequences, like doxxing.

In these same depositions, a CBP official claimed there were over two hundred CBP agents in Chicago, including “command staff.” Of those, one hundred were said to have received crowd control training. As distinct from the Chicago Police Department, which prioritizes crowd control and is fairly well-adapted to the local civil rights lawsuit ecosystem, DHS agents conducting abductions in the neighborhoods by and large lacked experience with crowds. This made them particularly vulnerable and erratic in street situations with heightened numbers of anti-deportation actors.

As a result, it became clear that the most effective tactical means of stopping a kidnapping was to gather a large crowd, distract, surround, and otherwise make the situation chaotic for agents, all of which occurred either during these spontaneous confrontations or extended tailing of caravans. Agents responded by using tear gas to cover their flight from the scene or prevent those they had already kidnapped from being dearrested, often hitting other cars in a rush to leave. In some instances, objects were thrown and used to block vehicles, and crowds generally made the feds’ lives difficult by getting in the way.

Ramming into people’s cars or using obvious caravans might not have directly helped CBP detain and deport more people. However, it did contribute to their other objective, just as important as numerical quotas or logistical milestones: picking spectacular, violent fights — always ones they expected to win easily — against unprepared, disorganized, or isolated onlookers, to terrorize the rest of the city into acquiescence. From the earliest days of White House “Border Czar” Tom Homan’s descent on Chicago, which brought Dr. Phil with a news crew in tow, this media-oriented strategy had been prominent and extremely difficult to disentangle from the simpler numerical objective.

Simply filming and heckling will not stop kidnappings. Spontaneous resistance during these standoffs was largely opposed by nonprofit leadership of ICIRR and OCAD, who argued that ICE was provoking confrontation and that, simply because ICE desired it, people should not actively resist or intervene in any way. After a responder who was tailing was first grabbed from their vehicle, and another was shot at in their car and hospitalized after being crashed into by an ICE vehicle, both organizations called for de-escalation and to stop following ICE vehicles. But for those who want to stop deportations, the bottom line is that resisting and winning will require confronting the feds.

Broadview

Before the announcement of Operation Midway Blitz, some turned their attention to the Broadview Processing Center, one of the few critical parts of the local immigration enforcement infrastructure. As ICE ramped up its operations in the city, reports of inhumane treatment flowed out of the facility — detainees held for far longer than the maximum three days, crowding, limited access to food, and a lack of proper bedding. The center processes pending deportations for the surrounding five states, and sees far higher activity than any deportation infrastructure in Chicago proper.

Early protests at the site were held on Fridays, when ICE reportedly bused detainees to the Gary Airport or other detention facilities. They were small and limited to heckling, sign-holding, chalking, and sacrificial sit-ins, which resulted in arrests by the local police. Following a similar model to anti-ICE organizing from earlier in the summer, efforts around this facility took an autonomous formation, which often invoked a “diversity of tactics.” In the Palestine movement, this concept had proven useful in defensive, rearguard struggles against more conservative, dominant, and established factions in campus settings.

At the outset of the anti-ICE struggle, especially at Broadview, the field was far more open; it meant people who wanted to abolish ICE had a seat at the table, but so did reformists, liberals, and collaborators. As the struggle continued, “autonomy” and “diversity of tactics” came to mean tolerance for anything and everything without a strategy or shared objective, while consequential, overriding decisions were made by a smaller, liberal, sacrificial faction focused on media and political influence.

In early discussions among coalition members, these participants leveraged connections and media presence to suppress others’ more militant tactics, deprioritize more radical points of unity, and emphasize recruitment over political clarity. These early concessions skewed the campaign towards spectacular activism and media spin. This compromised the group’s initial strategy, politics, and shared aim — closing down the facility and abolishing ICE — converting it to petitioning elected officials, getting brutalized on camera, and forging an unending series of alliances with dubious partners. It granted clergy, influencers, and aspiring politicians a leg up in the coalition, and it held back the politicization of those who no longer wanted to be beaten, arrested, or shot with less-lethal rounds — at least for its own sake. In a strangely ironic way, the project did develop autonomously — not from major nonprofits or political actors, both of which were allowed to determine its tactics and goals — but from residents of Broadview and from everyone who risked the most to struggle against it. Maintaining a “diversity” of conflicting viewpoints was, however, consistently used to shut down more radical participants and crowd out their projects and political critiques.

Looking back at moments of contention within the group, when liberals doubled down on prioritizing numerical growth, social media messaging, and depoliticized coalition-building, those who opposed them should have made the case for their own, opposed course of action and set of priorities. Instead, while numbers increased, strategy stagnated, more ambitious participants were consistently sidelined, and self-sacrificial tactics took scores of people out of a fight that had only just begun.

There are a few aspects of the struggle at Broadview worth highlighting. First, mobilizations began at the site in late summer and early fall, before CBP or the National Guard were mobilized to Chicago, which worked to our advantage. When Midway Blitz began, many agents who would have been on the streets profiling and kidnapping people were occupied with guarding the building and doing crowd control, a task for which many of them lacked training. As protest numbers at the site increased, DHS’s capacity and patience decreased, resulting in more indiscriminate use of less-lethal rounds and arbitrary arrests of our comrades. When Governor Pritzker deployed the Illinois State Police (ISP), he relieved the feds of their post at Broadview, and deportations and the usage of less-lethal rounds in residential neighborhoods went up.

Second, as the struggle continued, participants became braver and smarter at protecting themselves and others. Nearly a month after people began mobilizing at Broadview, a protest was called for the evening of September 19th. Geared up in black bloc, gas masks, goggles, and shields, people not only had the fighting spirit but were better equipped to handle the flash bangs and chemical munitions that had been indiscriminately deployed by ICE in the weeks prior, and later that day. While it signaled an elevation in militancy and a departure from the sacrificial tactics that had dominated the site, this militant high point lacked numbers.

In the days leading up to the 19th, those within the coalition who opposed confrontational tactics had formulated and spread prejudiced assumptions about the evening mobilization, and scheduled a moderate demonstration for the same day as the big mobilization, which affected turnout in the evening. The following week, likely in reaction to September 19th, they intensified their dissent by widely publicizing a non-confrontational protest, stage-managed by social media personalities and aspiring politicians. Cashing in on retaliatory threats made by DHS towards the residents of Broadview on the morning of the 27th, these aspiring personalities exploited local concern around ICE, labeling the action set for that evening and anyone planning to attend as “confrontational,” “making conditions worse,” and “endangering” locals. These gestures not only excluded working-class Chicagoland residents who wanted to fight the processing center, but they also undermined attempts to draw more than just the typical Chicago-based activist crowd, which boasts greater economic stability and flexibility on weekdays.

The presence of shields and attempts to throw back and extinguish munitions on the 19th inspired people in the weeks to come. However, it also inspired the agents to fortify the processing center by setting up a fence, expanding its boundaries beyond the facility’s property lines, and amping up the aggression. The following weekend, federal agents adopted riot control formations and sorties, maximizing their ability to deploy chemical agents and identify, charge at, and detain a handful of well-prepared people — singled out for wearing black bloc, holding a shield, or helping out others.

While images of their aggression drew more people to the site, DHS’s shows of force also successfully broke down more militant corners of the presence at Broadview. After a particularly violent weekend, in an attempt to control the site and slow the growth of its crowd, Gov. Pritzker sent ISP to Broadview and established “free speech” containment zones, which limited protests to sidewalks surrounded by concrete jersey barriers. With the ISP taking over Broadview’s defense, DHS deployed its agents elsewhere, resulting in less confrontation, as many regarded the ISP as reluctant defenders of the facility, rather than complicit enemies. With the processing center now out of reach, the aim shifted towards getting out of the free speech zones and back into the street instead.

A month after the introduction of ISP and physical barriers, a mobilization was called for November 1st. Its “minimum objectives were to overcome the trap of the self-sacrificial approach, to break out of the free speech zones and state-imposed barriers, and bridge the gulf between the ‘front liners’ and the rest of the protesters in order to be able to directly engage the police.” A crowd with a reinforced banner broke past the free speech zones and advanced on the facility, with regular, non-specialized participants following behind them. Like the weekend following September 19th, the reinforced banners were immediately confiscated, but people continued to occupy the streets. While a handful of front-liners stood their ground, others, mimicking Portland, began to line dance, many wearing inflatable suits. This seemed incongruous with the revived militant spirit and tone deaf, considering those kidnapped and crowded in the facility a few dozen feet away. But at least they were out there.

Nonetheless, the demonstration succeeded in breaking with the tactical norms demanded by the coalition’s more conservative members, and in blurring the distinction between militant frontliners and sideline activists by involving non-specialized participants. Unfortunately, this success could not last when set against the project’s downward momentum. For weeks, a small group of people had repeatedly chosen to chase media attention and political influence; these behaviors, combined with growing desperation, culminated in a meeting involving a handful of coalition members, the Governor’s office, and the head of ISP. Countermanding the larger group’s norms against talking to cops, they pawned off militants and anarchists to government officials by forewarning their threat, unless their demands — getting ISP out of Broadview and the charges against protestors dropped — were met.

There has been no considerable movement forward at Broadview since November 1st. People continue to flock to the site, but numbers are down, and the barriers remain. ISP, physical barriers, and now “free speech curfews” imposed by Broadview’s Mayor Katrina Thompson continue to hold back protesters. Many have since shifted their focus to local community efforts to intervene before people are detained and transferred to Broadview. Meanwhile, the federal government is moving forward with a plan to purchase an adjoining warehouse, increasing the facility’s size and capabilities while simultaneously complying with court orders to improve conditions and crowding. Ultras intending to return to the site will need to innovate to keep up.

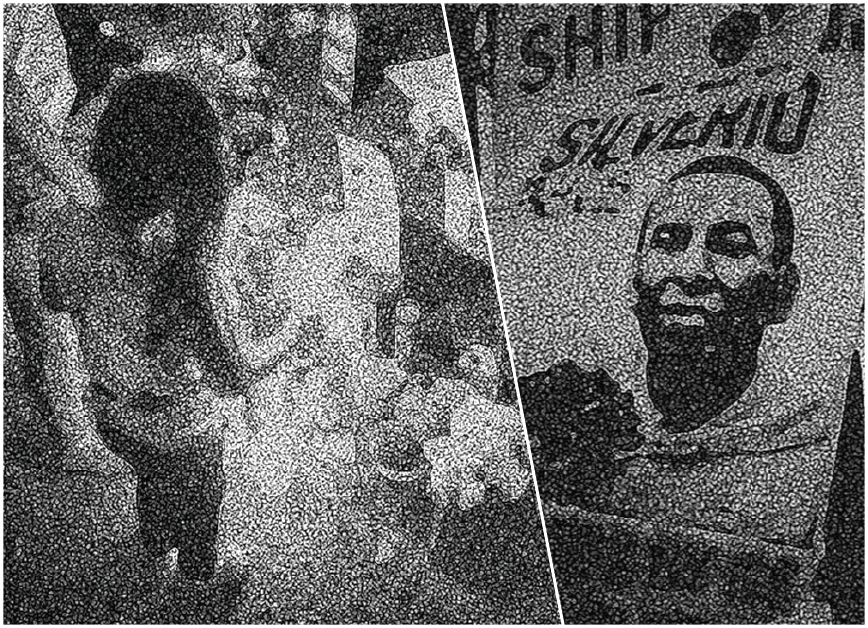

The Murder of Silverio and the South Shore Raid

On September 12th, Silverio Villegas González was shot and killed by ICE agents in the Chicago suburb of Franklin Park shortly after dropping his young children off at daycare and school. Villegas González arrived in the United States from Michoacán in 2007. The DHS attempted to justify his murder by calling him a violent criminal and claiming that he had used his car to attack the agents who had pulled him over. Neither of these claims was true: he had no criminal record at the time of his murder and was shot at close range while attempting to flee. This was far from the first death ICE is responsible for in this newest deportation campaign, as people have been hit by cars, chased off rooftops, and shot while attempting to escape from or film ICE agents. It was, however, ICE’s first murder during Operation Midway Blitz in Chicago.

For a certain section of the left in the U.S, especially those whose tactical and political consciousness was forged in the period of struggle bookended by Ferguson and the George Floyd Uprising, gratuitous police violence is understood as a potential spark that can light the dry kindling of unbearable immiseration and social tension. This can, and easily has in the past, become the assumption that open conflict with police should always be the goal, because it will elicit the type of police response — violence and even murder — that may spark a large-scale militant reaction. This theory of a dialectic of repression is a radical counterpart to the self-sacrificial, nonviolent civil disobedience strategy of spreading images of spectacular repression, often masochistically employed by clergy and liberals.

Much like its counterpart, this theory ignores the reality of ongoing gratuitous violence by law enforcement that sparks only suffering, not changed awareness or rebellion. The application of this theory by some in the ICE struggle in the United States reveals an inability to see this struggle for what it is, and a failure to reckon with the differences between this struggle and the ones that have played out between Black Americans and local police forces over the last two decades. The brief period of open struggle against ICE in LA earlier in the summer seemed partly to vindicate this perspective, but despite the killing of Silverio at the hands of ICE agents, one in a score of outrages committed in Chicago, no large-scale, militant response ever materialized.

To explain these differences, we’d point to concrete distinctions between 2025 and 2020, as well as the particular instantiations of the color line and citizenship in Chicago.

In 2020, the pandemic put millions out of work or compelled them to risk catching COVID-19 on the job, while global supply chains buckled under the increasingly global social crisis. This explosion of free time on one hand and plain deprivation on the other set the stage for millions to flood the streets in response to George Floyd’s murder, which tipped over into the score of uprisings across the United States.

Today, many can, and have to, keep working. For those forced to work or seek work despite their immigration status, the streets have in many areas become a mix of ghost town and war zone, emptied of as many people as can conceivably stay inside, under constant threat of being disappeared. When people have come out to try to stop a kidnapping in their neighborhood or joined a large street demonstration, this has not necessarily translated into larger-scale activity, let alone an “uprising.” Outrage at the murder of Silverio did not organically translate into political tasks or targets, and instead was followed by weekly vigils and art memorials. And in case it needs to be said, Broadview was not the Third Precinct; those who wished to see it that way squinted and only saw the small core of dedicated militants, ignoring the absence of a critical mass of everyday Chicagoans behind them.

Instead of explosive social rebellion, Chicago has mostly seen clearer and sharper internal divisions within the working class based on race, differing legal status, and countries of origin between more and less recently arrived Latin American immigrants, all against a backdrop of implied job and resource competition in a city of vast immiseration and segregation. This line was even upheld during the most despicable scene witnessed in Chicago this year. In the early morning of September 30th, federal agents raided a five-story apartment building in South Shore with helicopters and flashbang grenades, breaking down doors, destroying everyone’s belongings, and rounding up residents. Agents forced residents outside, bound them with zip ties, and segregated them, with “Black people in one van, and the immigrants in another van.”

This military-style raid in a predominantly Black neighborhood did not end the conception of ICE operations as limited to Latin American communities, nor did it lead to generalized struggle across racial lines. It was only five and a half years ago, at the end of May 2020, that shootouts broke out between Black and Latin American gangs over the looting of stores on the West Side; to our knowledge, except for a rumored “hit” ordered on Bovino by a Latin King, there has been no apparent anti-ICE activity from these street organizations. Internal divisions have only increased since 2020, especially after the arrival of tens of thousands of Venezuelan immigrants from Texas and the subsequent strain on Chicago’s social service provisioning, with no present indication that they are being overcome, or any reason that they would be automatically, absent a political intervention that can compete with the autarkic scrambling for resources encouraged by the state and civil society.

Repression and horror alone don’t spark rebellion. Nor does the experience of oppression translate neatly into support for liberation. Instead, those not under immediate threat will only become active opponents of the border regime when they realize their own freedoms are being trampled upon, not just those of migrants, and choose to struggle with them, against whatever petty rights and privileges are afforded to them by race or citizenship. Those in favor of a revolution in the U.S. can and should struggle and agitate around this realization and the conditions that can exacerbate it, but we cannot engineer it.

Centros

Later attempts to expand the struggle at Broadview into a larger campaign with national repercussions occurred almost entirely among activists and already politicized people. As Broadview hit wall after wall, especially after the arrival of ISP, some decided to refocus on neighborhood-level community self-defense. People adopted a tactic from Los Angeles: returning to their neighborhoods with street-fighting skills and renewed dedication to form local defense hubs at frequently-targeted ICE hotspots, most commonly hiring sites for day laborers. This has brought the struggle against ICE the closest it’s ever been to facing the class- and citizenship-specific dynamics that actually determine the distribution of terror, violence, and deprivation we’re seeing meted out by federal agents.

In Los Angeles, comrades at these hubs built relationships and trust with migrant laborers and helped boost the neighborhoods’ pre-existing strategies to prevent kidnappings. In some places, these looked like tables with resources and a handful of volunteers with whistles, while in others, it expanded to provide mutual aid and organize patrols of the surrounding area. In Chicago, this was not just an opportunity to help develop ICE watch, but also to help create infrastructure for broader, more proactive community defense.

This pivot was most attractive for rapid responders who found themselves burnt out from monitoring group chats, following sightings, tips, and false alarms into oblivion, and usually never encountering ICE. As this high-investment and low-payout tactic continued to churn, people visited hiring corners to inquire about where people were assembling, when they were most numerous, and ICE’s patterns in the area, to determine how to translate this Los Angeles tactic to Chicago.

At many of the most promising locations, the number of day laborers had already dwindled from twenty or thirty to three or four a day. Either undocumented people were being picked up at home by their bosses, the risk of looking for work that way was no longer worth the risk, or they had been abducted, held, and deported by ICE agents weeks ago.

In Chicago, before Operation Midway Blitz, the Latino Union’s Adopt a Corner program called for people to set up ICE watch at Home Depot locations. There were also a few autonomous efforts to set up centros, and likely other similar neighborhood-level projects that never made contact with the fairly rarefied social world of Chicago activism. A centro was announced at the Home Depot at 47th and Western in October, with a table, resources, and coffee, and a few others have emerged since, including one on the northwest side at Belmont and Milwaukee in November.

During raids near centros, people were not always able to stop ongoing kidnappings. However, they did immediately alert others to run, and successfully stalled, impeded, and chased off agents. During raids, volunteers and strangers alike would let centro volunteers jump in their cars, follow ICE, and chase after vehicles. In some instances, people were able to block and stall ICE vehicles, allowing cars tailing the feds to catch up. During larger confrontations, centros enabled people to plug in and get a whistle immediately. People engaging in different tactics were supported by the trust built through daily presence.

Divisions around the color line and citizenship continue to impact the development of centros in Chicago. The first centros in Chicago developed on the Southwest Side, in an area with substantial community support. But community defense on the predominantly white and wealthy North Side, where workers are abducted more from job sites themselves, poses different challenges to establishing a centro. And on the South Side, divisions within and between communities have contributed to paternalistic, nationally-limited, or class-based approaches to anti-ICE organizing that do not actually involve many of the people most targeted. Meanwhile, throughout the city, rapid response has at times resembled neighborhood watch, monitoring “suspicious” vehicles armed solely with race- and class-based assumptions.

Despite a general willingness to support actions that force the feds to leave, there is a general lack of shared antagonism towards the cops. Among many volunteers, neighbors, and vendors, the federal occupation has only increased their loyalty to local law enforcement and officials. Even cops say things like “Don’t worry, we aren’t ICE.” Centros have not overlapped with copwatching so far, and when people have copwatched, onlookers have been far less willing to intervene. Importantly, however, while many people still believe in the benevolence of the local cops, day laborers generally do not share this misconception.

The biggest logistical challenge has been sustaining numbers, particularly at locations with less community support. Day laborers themselves were often quick to spot ICE, but sprinting away after an alert wasn’t enough, as agents began tracking workers down to nearby hiding places and scoping the area via helicopter ahead of raids. More participants allow more lookouts and faster alerts, and, above all, with greater numbers, a centro can carry out more successful interventions in kidnappings, whether that’s through distraction and getting in the way, helping neighbors hide or escape, or something else entirely.

At this stage, centros in Chicago are very new, ICE hotspots are numerous, and sustaining significant numbers at any given location is difficult. It is unclear how durable they’ll prove during the winter or as time goes on, but they could lay the groundwork for place-based strategies that last beyond the present moment.

Of course, this is just one piece of the puzzle, and turning to hyper-local, neighborhood-level organizing among working-class Chicagoans will not necessarily change the political composition of the movement against ICE. We lack a clear, appealing vision for social transformation that could rival any of the others on offer, all of which spell barbarism and common ruin. It’s our responsibility to stake out a competing position, one that connects this particular struggle to a future free society, which refuses the Republican Reich’s racial purity program as well as the sacrificial half-measures on offer from the Democrats.

In particular, the centro model has also hit the same limit that every other social movement since the late seventies has eventually encountered: the split between production and reproduction, broadly construed. What “labor movement” activity still exists sets its terms and evaluates its successes in purely “economistic” terms: revindicative struggles over higher wages, better hours, or more appealing conditions. Likewise, social movements have their own barometers for success, which they’ve largely inherited from activist nonprofits and pressure campaigns: numerical thresholds for participation, successful provision of some service to some number of people, or spectacular direct actions intended to broadcast some message.

For their part, centros concern themselves with all of the conditions of everyday life that take place before a day laborer gets into a car and goes to work: by supplying umbrellas and jackets, hand warmers, coffee, and breakfast when possible, and ultimately attempting to deter state terror that attempts to drive day laborers away from their hiring site. All of those tasks and obligations tend to technically specialize those who staff the centro and implicitly divide them from the people they are designed for — and, as a result, tend to deform it to its closest nonprofit cousin: service provision. Volunteers at centros find themselves standing outside of the production process, guaranteeing precarious day laborers’ entry to jobs that will invariably expose them to degrading and thankless drudgery, risk further harassment by ICE, and try to stiff them on pay at the end of the day. The closest thing to intervening in the production process is helping workers negotiate over pay as they enter vehicles.

Centros could be an opportunity to challenge this sharp division between the production process and well-intentioned activists who tend to stand outside of it. Currently, the centro is an empty container that facilitates any activity by interested parties. This is one of its tactical strengths, but it also makes it easy for a preponderance of nonprofit-minded activists and staffers to sway its direction towards service provision. What excites us about the centro model is its potential; during moments of upheaval, autonomous infrastructure like this, if it were clarified politically, could launch new experiments in local autonomy and self-management, antagonistic to capitalist social relations and the state. This would be built and sustained by those who need it, not just concerned citizens or neighbors who staff it for the sake of those it benefits.

These experiments in self-management would require settling on a third set of standards for self-evaluation — not the ones we’ve inherited from brief moments of empowerment in our workplaces or flashy social-movement successes, but drafted instead with a completely different goal in mind: the realization of a dignified life in common. Economic achievements and social movement successes would not be measured in terms of pay raises, better hours, thousands of marchers, or hundreds of lunches packed. Tactics would be pursued and prioritized based on whether or not they strategically contributed to our ability to reproduce ourselves without money or wages, or to the revolutionary abolition of the state and the economy.

If we want to act effectively in this context, we have to start by being honest about our politics. This means making our ideas practically salient and finding ways to test our hypotheses that take hunger and captivity, not ostentatious displays of intellect, as their motivating force.

Think Again

With the release of Francis Ford Coppola’s 2001 Apocalypse Now: Redux, audiences learned that Lt. Colonel Bill Kilgore never gets his day of surfing. The napalm with which he scorches an entire beachhead village in the name of neo-colonial American sport also spoils the wind and renders the purpose of the whole massacre moot. While we may hope for such cosmic justice meted out against those terrorizing our city in the name of herrenvolk democracy, we aren’t taking any chances. No matter how impossibly impersonal the unfolding of the past year might have felt at times, we have not given up on the subjective element, the possibility that small numbers of like-minded participants can help shape the unfolding of events.

To this effect, we will have to fight smarter and better in 2026 — putting our phones down, turning our brains on, meeting more people, and pinpointing the tactics that are both effective and suited to developing a revolutionary strategy. In Chicago, both local community defense and offensive actions targeting deportation infrastructure will be necessary. Both have proven more effective than roving patrols or tech-based rapid response, while also helping participants build trust with one another and discuss longer-term political objectives, albeit slowly. Hypothetical offensives against the deportation process, however understood, require a proactive analysis of regional detention infrastructure, widespread dissemination of information about relevant sites, and strategic considerations of weaknesses and possibilities: how easily can the location be reached? Is it federal or private property? What is its importance to the broader network of deportation infrastructure? And are those who want revolution ready to capitalize on the successes they achieve at these sites?

As we finished these reflections, Nenko Stanev Gantchev, a Bulgarian resident of Chicago for many decades, died in an ICE detention facility in Michigan after agents neglected treatment he needed for his diabetes. As the death count of ICE’s enforcement and detention camps rises, often in rural and hard-to-reach detention centers, the question of what measures need to be taken looms large. And as repression of resistance — notably the 18 Prairieland Defendants held under terrorism charges — increases, with more federal resources dedicated to investigating and prosecuting “antifa,” ultras must honestly weigh the risks of sticking to small crews and operating primarily within “vetted” environments against the risks of being honest about who we are and what we believe with others who appear different from us.

Revolution will require millions of people coming together, united in their aims, overcoming the real and objective divisions that presently render them impermeably separate, to pursue a long, difficult, unsafe project with uncertain prospects. The kind of political relationships necessary to weather this kind of intensive struggle over time must be rooted in respect, trust, and good faith. When large membership organizations and nonprofits treat their members as pawns, locked out of decision-making and manipulated toward ends known only to a small elect, we rightfully dissent.

There is an equal tendency on the far left to fetishize politics as the domain of secretive social cliques whose relationship to broader masses, including other comrades, is insular and conspiratorial. The particular ideology animating these “invisible pilots of the revolution” is besides the point; anyone can do it. What matters is that nothing can trick people into carrying out a revolution, and no artificial pressures can create its necessary conditions out of thin air.

This is not a moral argument; it is a practical one. Trickery is simply an ineffective long-term strategy. Even if they successfully achieve short-sighted goals, political tricks are often obvious and alienate potential comrades for years thereafter. Nobody who believes they are being led through a hall of mirrors will tolerate it for long. Let’s be honest: How many conflicts in political scenes across the United States, and beyond, originated in resentment stemming from the perception that one crew was relating to others in bad faith, as a means to an end? There are, of course, security reasons for keeping certain matters on a “need to know” basis. The brass tacks of illegal activity should be known only to those poised to act on them. Sometimes, crews operating within a broader movement where there is not sufficient trust may elect to keep their identities secret. But these are tactical decisions, not a strategic imperative.

As we went through the year, what often hampered us the most were our inherited sensibilities. In 2025, retreats into affinity-based political organizing, an emphasis on “opacity,” and an exclusive focus on tactics at the expense of this situation’s emergent, class-level strategy, while necessary correctives to ward off social-movement managers and budding professional activists, have left us marginal and isolated. We have seen crews end up effectively apolitical and regularly mute, unable to share their thoughts with anyone, even comrades, let alone convince others that their goals are desirable. We’ve got to stop enjoying our own obscurity.

Signal threads are full of ever-changing non-sequitur usernames, making it difficult to know who you are talking to, much less to get in touch with someone specific when you need them. Use of one-time noms de guerre in meetings, in addition to the movement-specific names many already have, often only increases the confusion. In even the most innocuous street situations, disguises are worn at all times, making long-term relationships difficult, even among committed radicals, much less between them and others outside radical scenes. Basic practical questions are treated with suspicion, and the possibility of a serious discussion of strategy is nonexistent. The most paranoid impulses of insular activist scenes are running rampant and exacerbating longstanding trends of decomposition and attendant marginality. We have become water and evaporated.

It doesn’t accomplish anything to pretend otherwise. For instance, there might well have been an opportunity for a large-scale, militant mobilization around Broadview in the early days, before ISP showed up to back up their buddies in Trump’s Gestapo. But if there was a coherent and clearly articulated strategy around Broadview, shared throughout the radical milieu, that the rest of us failed to sign on to — that’s news to us!

This muteness cost us in 2025 and has led to widespread confusion about what we are fighting for. While it may be prudent, for instance, to collaborate with those who hold very different political views to achieve tactical aims, like organizing actions or maximizing presence at a particular hotspot, our objectives are not to pressure Democrats or revitalize the Democratic and nonprofit machines in a “big tent” against fascism — always big enough to turn radicals into shock troops, and always capable of shrinking to exclude them when they start thinking. The sad fact is that the Democratic political class and “progressive” civil society organizations are not our prospective allies but rather another sector of opposition. And if we subordinate our politics to electoral pressure or limit our activity or what we say about it, we can’t expect anything to change.

Ultras in the anti-ICE movement, ourselves included, did not speak up enough in the first place to communicate our own objectives, or double down enough when encountering conservative, “back-to-normal” politics within the so-called “big tent.” This kept potential allies from knowing we existed, much less finding us. Revolutionary goals will succeed or fail depending on whether millions of working people decide that the benefits of a potential future society outweigh the misery and drudgery of remaining in this one. They won’t even consider the decision if we can’t articulate what’s possible. This was a lesson we learned in miniature at 2024’s Palestine encampments, only to run into it again, “off-campus,” but still unresolved.

We write at a curious juncture. On December 23rd, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Illinois and against the federal government’s assertion that they are right to deploy the National Guard in Chicago. Meanwhile, Illinois protestors who have faced charges, ranging from obstruction to assault, have steadily seen their cases dismissed, dropped, or refused to be taken up by grand juries. In many of these situations, video evidence supposedly proving the protestor’s “nonviolence” is used successfully by the defense. Illinois has argued that the National Guard is not needed because the protests against deportations are “nonviolent” and do not constitute “obstruction.”

Is this true?

Justice Kavanaugh, who concurred in judgment but would have ruled on different grounds, anxiously outlined a scenario where the National Guard would need to be federalized as promptly as possible, if the military were not immediately available:

Suppose a mob rapidly gathers in response to an unpopular decision (or to influence the outcome of a pending matter). Suppose also that the mob is threatening to storm the courthouse and attack the federal judges, prosecutors, and other personnel inside, and to damage or burn down the building, thereby preventing the execution of federal law. Suppose further that U. S. military forces cannot readily mobilize to deploy to that site in time, that the local police and federal court security officers are outnumbered, and that the President wants to federalize National Guard units to protect the courthouse and the judges, prosecutors, and other personnel. Under the Court’s order today, even in those circumstances the President presumably could not federalize the National Guard…

These are the two options legible to the ruling bloc: on one hand, pure commitment and moral fiber expressed in nonviolent civil disobedience; on the other, disorganized and spontaneous violence directed at federal targets.

Both of these may be on offer, but neither is sufficient. Kavanaugh’s anxiety is that the “mob” would accomplish a single, tactical victory against a federal courthouse — after which the military would arrive and quickly suppress the revolt. Those in favor of social revolution in the United States ought to dedicate themselves to outlining a third option, which turns expressions of popular rage into the first steps in a potentially revolutionary sequence, pursued not just to destroy one site of federal power but to topple the federal government itself.

TL;DR / Takeaways

- Tech-based rapid response networks and patrols (without specific strategic purposes) are a red herring. Consider the best uses of your time/resources and build real connections at high-risk locations. Developing place-based community defense can foster trusting relationships and help create the conditions for people to be present for raids and stop them. They could also develop into revolutionary infrastructure for mutual aid and life without the state and economy.

- Identify relevant infrastructure and disseminate that information. Learn what you can about where immigrants usually assemble in your area and what might happen to them if they get kidnapped by ICE.

- Treat anything IRL, including rapid response, as a potential space to cultivate real, continued trusting relationships. Meet your neighbors, build relationships and skills, and form a local group with political orientation and grounding that can expand into diverse projects.

- Do what’s practical and productive. Outside of unproductive patrols or tech-based rapid response, tailing vehicles proved to be a useful tactic when it provided real-time updates on ICE and allowed people to intervene.

- Exploit the lack of crowd control training among agents to develop unmediated community intervention at the neighborhood level. Create chaotic situations for agents that make them want to flee, like creating distance between agents and their cars. It might freak them out and make them retreat without abducting their target.

- All skills should be de-specialized. Gatekeeping action, or deferring action to those who deem themselves specialists, is damaging to the movement and must be resisted. People should be empowered to take action themselves, without management; skills should be taught with independence and autonomy in mind.

- Tactical sensibilities based on city police or riot police won’t always be appropriate. ICE/CBP acts differently and is equipped differently.

- The anti-ICE movement is different from an anti-police movement. Race, citizenship, and legality function differently, and this can not and should not be forced to fit an “Escalate” model; nobody should engineer repressive situations with the intent to mobilize future crowds, or trick people into doing political things.

- People act conservatively when there is nothing more appealing for them to do. Ultras need to disseminate information about alternative activities and do them.

- Make connections with people who aren’t already like us, but don’t de-emphasize revolutionary politics to grease the wheels. “Diversity of tactics” and “autonomy” can quickly lose content and place us back into the situations these phrases were intended to get us out of, where collective activity is tightly controlled, and political criticism is impossible.

- Reject de facto big-tent political alliances with “progressive” civil society orgs and wings of the local political class. There are tactical reasons to align with members of these factions in specific moments, but this is not the same thing as folding our strategies into theirs. Pressuring Democrats is neither our job nor our intention.

- Intentionally combat frantic activist activity. Things feel urgent, but we can’t act as if everything is urgent — people get burnt out, paranoid, and unable to think strategically. It is essential to build trusting relationships and expand social networks so people can skill up and act together. This can feel at odds with the apparent urgency of the situation, but continued effort without stepping back to reflect is energy wasted.

- Ultras should not conceal their politics. We are in a social crisis, and believe social revolutionary politics can fundamentally shape its outcome. When our opponents double down on their politics, we should do the same.

The Struggle Continues!