by the LAKE EFFECT COLLECTIVE

The final Gaza solidarity encampment to fall in the city of Chicago was pitched on June 8th at Buckingham Fountain, directly adjacent to Lake Shore Drive and within sight of the expanse of Lake Michigan. An hour and forty minutes into a small rally, a group of participants hurriedly set up a dozen tents, established a new “encampment,” and “liberated” the fountain in the name of Gaza. Chants included: “We will protect our students.” However, the Coalition for Justice in Palestine (CJP) did not show the camp the same loyalty; after ushering a handful of over-eager arrestees out of the tents, organizers with CJP unilaterally called an end to the rally. The Chicago Police Department (CPD) followed on its heels to confiscate and discard the tents once the camp had voluntarily disbanded. The fountain was “liberated” for a few hours at most. The tents, leftover from other encampments, which CJP had refused to donate to unhoused Chicagoans because they belonged to the organization, were instead gifted to the CPD—who did not appear to appreciate the contribution.

This bizarre conclusion to a semester of campus occupations is how exactly half of those who planned the University of Chicago Gaza Solidarity Encampment hoped events would conclude on their quad. These student activists, who made up a vocal reformist bloc within the so-called “Core” of UCUP (University of Chicago United for Palestine), promised to stay until the school divested from Israel. For many of them, it was a bare-faced lie; they planned to return to their dorms and apartments after the camp’s second night. This faction subtly campaigned against keeping the encampment going for its entire existence and consistently wore down efforts to make it a genuine occupation.

They were, however, a numerical minority. Many students heard their cynical words and took them literally, as the promise to stay until divestment became the bottom line for the encampment’s radical edge. The tensions that emerged between the phrase and its content, as Core’s internal unity and external control of the camp’s affairs broke down, helped us find our place among the various blocs of the campus-based Palestine movement. We hope an inventory of these experiences may point to possible ways forward now that the season of encampments has ended.

The document you are reading is the direct collaboration of eleven participants in the encampment and draws upon insights and recollections from a larger body of comrades. While we use an authorial “we” to outline points of consensus, the authors are an eclectic group of UChicago students, workers, and unaffiliated community members. Some of us have extensive movement activity, including Palestine solidarity, labor organizing, and campus politics, and others experienced the encampment as their first wave of struggle. Many of us did not know each other before the encampment, and we are not members of any revolutionary organization. Despite our different backgrounds and varying relationships with the university, we came together around a shared practical sensibility, steered by the notion that the Palestine solidarity movement in Chicago, and more broadly, the essentially connected movement to end capitalism, must do better, and develop tactics and strategies adequate to these righteous aims.

We believe that the university encampment movement in the United States is a significant political development that will, for better or worse, determine the immediate future of the Palestine solidarity movement and also help set the stage for the next wave of mass struggle on a more generalized scale—the likes of which we saw in 2020 and will surely see again before long. It is thus essential to map its contours and contradictions. In our narrative analysis, we hope to establish a definitive documentation of how the UChicago encampment went down, with the broader intention of opening up an array of tactical and strategic questions for readers in Chicago and beyond. We offer a story that is at once likely to be familiar to those who have participated in pro-Palestine encampments and simultaneously quite at odds with the official version of events offered by the more reformist organizations active in them. While certain aspects of the story are unique to their setting, most of what we have included is generalizable to pressing questions around how incipient mass movements understand themselves, organize, unfold, and die. Within the context of UChicago, we hope what follows will serve as a kind of cautionary tale. The movement must do better in the future, and we would not have taken the considerable time to collectively author what follows if we did not believe it was possible.

While we do not have a directly programmatic solution for the present political morass, we share a common understanding that the only effective movement to free Palestine must simultaneously entail the revolutionary transformation of the United States and all capitalist societies, on which the barbarism of Zionism and other forms of life-denying oppression rest. This understanding does not mean deferring the end of the occupation until the proverbial “after the revolution,” but instead, practically linking the fate of Palestinians with the victims of capitalism on a global scale as a means of orienting political activity on the local level, in the here and now. While overthrowing a superpower like the United States and the attendant collapse of the capitalist mode of production might seem impossibly far-fetched, such abrupt historical transformations have almost always seemed that way until the day they didn’t. In any case, this is not a thought experiment; the struggle is already underway.

I. The Siege of Gaza

In 2024, the Zionist state has occupied the land of Palestine for seventy-five years. For three generations, the regime and its armed men have subjected Palestinians living in this reservation-turned-killing zone to deprivation, humiliation, and genocide. But the blame falls on the Zionist entity only as much as it falls on its friends, those pioneers of population management: the last centuries’ colonial empires and their descendants, the developed capitalist states. Once eager to support the creation of a “national home for the Jewish people” Somewhere, Anywhere But Here, these states now constitute the Zionist regime’s most earnest and ardent supporters, seeing it as a crucial partner and foothold in a crisis-ridden region, at various moments the bulwark against communism, Arab nationalism, and political Islam. The history of the Palestinian occupation is a global story, implicating the great powers of the world; so, too, must its liberation be the business of every person fighting for freedom worldwide.

The present historical moment began in the late twentieth century, with powerful nations and increasingly transnational capitalists realizing that the world system sustained until the sixties and seventies could not continue. Profit rates dwindled, and state counter-offensives against radical labor and liberation movements triumphed domestically. Capital then set its sights abroad, as industrial manufacturing in the core gave way to a bloated service sector and ejected swathes of (racialized) proletarians from regular access to employment and pay. Simultaneously, colonies and dependent client states won their “independence” from their metropoles, only to be re-integrated into global circuits of capital by the same imperial firms fleeing their domestic labor markets, backed by an international order capable of forcing newly independent states into predatory “structural adjustment” policies, responding with extra-economic force where this proved unsuccessful. This new round of primitive accumulation engendered perpetual instability in many so-called underdeveloped nations as a paramount condition of their participation in the world market. To make matters worse, the drive to compete has accelerated the destruction of a massive range of the planet’s plant and animal life and rendered human habitation in these same areas increasingly dangerous—for their inhabitants and the rest of humanity, as the four-year pandemic has demonstrated.

We face a combined but unequally developed global crisis at the hands of a transnational capitalist class whose “ruling bloc” is politically disorganized, incapable of or unwilling to pursue long-term planning, and ready instead to white-knuckle whatever crises are necessary to shore up its persistence, at the expense of the populations it holds apart from regular employment (hereafter “surplus” to labor). Avenues of resistance—labor unions, old socialist parties—that once served as counterweights to the capitalist order have been integrated into it. Likewise, the external differentiations that once characterized global politics have fallen to the wayside as part of an international consensus to safeguard new accumulation schemes and protect the system from its final collapse. Unlike the left, which is disoriented and dislodged from the old institutions and conditions of struggle that gave the old workers’ movement shape, the world’s leaders find relative unity in the willingness, among a handful of competing blocs, to deploy the same technologies of surveillance, incarceration, internal and external policing, and war to bolster their territorial claims and the interests of their more prominent individual capitals.

Occupied Palestine is one laboratory among many for maintaining affluence amid this sustained crisis. Following the 1997 establishment of the Greater Arab Free Trade Area and the 2003 invasion of Iraq, capital in the Middle East has consolidated—as seen in the 2020 Abraham Accords normalizing relations with the UAE and Bahrain—and been integrated into global circuits. The Zionist entity is also on the receiving end of large flows of migrants from Africa and East, South, and Southeast Asia, drawn on to implement its projects. Notably, the majority of Palestinians in Gaza have not been permitted entry to work since 1993, when the Zionist state sealed Gaza’s borders following the first Intifada. During the decades following, the regime began “To reorganize labor markets and to recruit transient labor forces that are disenfranchised and easy to control.” In particular, migrant laborers replaced Palestinian surplus-proletarians as a flexible and cheap labor market input, rendering the present genocide economically feasible in light of the global integration of border regimes and increasingly transnational labor markets.

Globally, migration rates have skyrocketed as those who can escape for more stable and temperate zones with more capital and competitive labor markets do so. These migrants are at once shut out and drawn upon as needed to implement what the managerial middle class has determined is necessary to maintain bourgeois consumption standards; they serve as floating labor reserves for increasingly predatory individual capitals. From the American Southwest to Australia, core states have accomplished in their border enforcement what was once only achievable through apartheid. Likewise, migrant laborers in Israel “do not need to be subjected to the apartheid system imposed on Palestinians because their temporary migrant status achieves their social control and disenfranchisement more effectively, and of course because they are not demanding the return of occupied lands and do not have a political claim to a state.” This ejection from access to labor markets leaves the Palestinian people not as a traditional surplus population, leveraged to keep the price of labor cheap, but as surplus humanity, split off from the cycle of capital accumulation that binds Israel to the rest of the world system. On this point, the imperatives of international capitals and the Israeli settler state happen to agree—though it would make little sense to imagine the genocide in Gaza as driven by purely economic motives.

Fueled instead by a combination of economic imperatives and deranged ethno-religious fundamentalism, the genocide is a war of annihilation that attempts to empty Gaza of native inhabitants by a combination of maximal mass murder and minimal forced ejection, after which the entity will convert the land into space—“a parking lot,” in the words of some American officials—imagined by some as the future site of an Edenic paradise. But it is not clear whether these fantasies of resettlement will outlive their ideological shelf-life: attempts by settler factions to enter the north of Gaza during the opening of the genocide were not enthusiastically endorsed by the state, for example; at any rate, the wholesale destruction and ecological devastation wrought by the military invasion will render any future resettlement in many places difficult if not impossible. To our understanding, 2005’s “disengagement” and the shift to Gaza’s Bantustan–like status sidelined settlement aims in Gaza. The presumption that the settlement-driven wing of Israeli civil society and the annihilationist techniques of the Zionist military are in agreement on the long-term goals of the genocide assumes that an ideological agreement among parties suffices for a shared strategic vision of the settler state’s future. We should not underestimate the political and cultural divisions that may lead the so-called Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) into a blind alley.

In occupied Palestine, then, we see a grim vision of the future: an increasingly ecologically endangered racial regime with a fascistic white population clinging to its consumption standards with a controlled rate of migration from racialized external populations. Some laborers are stuck at the border, while some are permitted entry conditional on their below-market-average employment and often backed into unthinkable labor conditions by their employment-conditional visas. An internally immobilized, racialized population converted from labor surplus to mere obstacle—now facing genocide as punishment for a refusal to be penned in and killed at will. Economic forces alone do not explain the zeal with which Israelis are liquidating their neighbors; the murderous, settler-colonial ideology of Zionism provides a visceral and emotionally charged political identity through which the aggressors in a century-long genocide, armed and supported by the most powerful nations in the world, may view themselves as underdogs and victims as they mete out the very atrocities they accuse their victims of perpetrating.

After decades of repression and slaughter, what remains of revolutionary resistance in Palestine? Since October 7th, Fatah, the largest group within the Palestine Liberation Organization, has remained silent, as its goal of peaceful compromise with America and the Zionist state has failed. The Marxist-Leninist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), historically the voice of the Palestinian revolutionary left, declined in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Bloc and, more importantly, since Israel split off Gaza from anything approaching a labor market integrated into its national economy. In the gaps left where historically secular nationalists and communists stood, Islamic resistance groups like Hamas have surged in popularity. Like Fatah, Hamas has always been a free-market, nationalist, capitalist party: it raises its funds through heavy taxation, and its wealth lies in investment portfolios held primarily in Turkey and the Gulf states. It has risen to power as the floor fell out from under the conditions that supported the old vehicles for struggle and as every other path of resistance has been met with extreme repression. It is not, however, the only participant in Palestine’s armed struggle–October 7th’s Al-Aqsa Flood was planned and executed by a coalition of armed organizations, and subsequent demands by spokespeople of the Palestinian resistance demanded the freedom of non-Hamas political leaders as well as Hamas affiliates.

Last January, the New York War Crimes ran a fascinating piece exploring “The Black Liberation Movement and the Struggle for Palestine.” The paper translated a statement by Abu Ghassan, the imprisoned Secretary-General of the PFLP, which proclaimed “[f]rom inside the occupier’s Ramon prison” that from “Ansar to Attica to Lannemezan, the prison is not only a political space of confinement but a site of struggle.” Throughout the wave of encampments, these functional ties between American and Israeli police and prisons have been emphasized rhetorically by many activists. However, the issue’s politicization has often stalled in identifying a common enemy instead of entering into the conditions of struggle that unite and separate Gaza from places like the South Side of Chicago.

The lessons we might learn from the Palestinian resistance require translation into our domestic conditions. For instance, while Palestinians have been severed from Israeli labor markets nearly entirely, the continued yet precarious employment of Black proletarians on Chicago’s South Side, while they are at the same time managed, killed, and caged, indicates their fragile relevance to domestic individual capitals outside of the prisons has not yet run out. In an increasingly interconnected world, the same system metes out death and devastation to these geographically separate populations. It will only be through common struggle across these and many other lines of globalized class stratification that we can decisively defeat capitalism. Resistance is everywhere, and this resistance must be generalized, clarifying in the process its enemy and the “we” who oppose it.

In America, as in Palestine, struggle is defined by the contradictory character of the people and groups who make it. The political limits of our times are the limits of the class fractions who command and system-level restructurings that define the terrain for the movements we enter into—in Palestine, the decline of the revolutionary left and the rise of liberal-religious armed struggle factions following the Zionist state’s slide into crisis-ridden restructuring. In America, similar economic transformations deformed rebels into a new category: the activist. In the 1990s, following the twilight of the workers’ movement and whatever had existed of a revolutionary left, people adopted a model of political struggle to match the time: the corporate campaign, in which depoliticized participants accidentally united around short-term tactical questions related to fighting an individual corporate entity, absent a broader transformative vision. Most famously, environmental activists around the turn of the 21st century adopted this model, and it has more spectacularly re-emerged with Palestine Action’s sabotage campaigns against Elbit and the PYM’s #maskoffMaersk campaign. Its foundational assumptions also define the basic organizational unit of the campaign for the boycott of, divestment from, and sanctions on the state of Israel. Piecing together the mark of this organizational form on ‘campus activism’ will help clarify the limits and potentials of the campus-based struggle for Palestine.

II. Bring the War Home

While the U.S. wing of the movement opposing the colonization of Palestine predates the state of Israel itself, it suffered a lull after the defeat of its proponents in the Black Power movement during the 1970s. Flurries of activity briefly punctuated this overall decline in action and consciousness in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle in 1982 in opposition to the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and, to a lesser extent, in 1993 following the betrayal of the First Intifada through the Oslo Accords. In the early 2000s, when the anti-war movement in the U.S. connected with the Second Intifada in Palestine, this movement experienced a wave of new organizing that would prove more durable than previous iterations–particularly on college campuses.

In 2002, the previously marginal Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), founded in 1993, saw an explosion in its membership, spreading to campuses across the U.S. SJP inherited a strongly decentralized structure from the 1990s, designed to allow for political work among a deeply politically divided constituency (analyses of the state of Israel as a settler-colonial apartheid state, or of the two-state solution as a dead-letter cover for worsening settlement of the West Bank, were still hotly contested within the movement at that point). This largely uncoordinated but ultra-visible activity of Palestinians and anti-Zionists on campus had provoked a reaction from Zionist politicos and funders: students founded several new Hasbarist organizations with explicitly campus-focused missions in response to pro-Palestine student groups. Building on this work, the David Project waged a ruthless fight against anti-Zionist scholars starting at Columbia University in 2004. On the other side, in 2005, a coalition of Palestinian trade unions and civil society organizations released the call to Boycott, Sanction, and Divest from those responsible for the ongoing ethnic cleansing of Palestine, providing the fledgling student movement with a unity of purpose which persists in the movement today. Within a few years, campuses had become the central battlegrounds in the ideological fight over Zionism and Palestinian self-determination in U.S. civil society.

SJP’s influence, and that of the BDS Movement, only grew in successive years as Israeli politics lurched to the right, producing multiple new offensives on Gaza. Since the start of the Second Intifada, no student has completed a 4-year course of study without a significant incursion by the IDF into Palestinian territory and an accompanying massacre of Palestinian civilians. In this context, BDS has proven remarkably effective at shifting popular consciousness around the Palestinian struggle and laying the groundwork for the current outpouring of anti-Zionist resistance. This conjuncture has produced an overwhelming political shift, particularly on campuses, where large majorities of constituents were young enough not to have been politicized during an earlier period of hardened pro-Israel hegemony, with more obvious localized stakes, targets, and demands of the struggle for Palestine.

Meanwhile, the past decade of campus activism has proven inseparable from the growing realization within American civil society that its history, culture, and state are bound up in a white supremacist labor regime that condemns whole strata of its population to unyielding misery. Student critics of their client universities are increasingly encouraged to articulate their grievances in the theoretical registers of settler colonial studies and the Black radical tradition. It is thus unsurprising that the movement of the encampments that captured the imagination of the U.S. left and that saw some of the most militant, most advanced confrontations with the state since the 2020 George Floyd Uprising emerged on college campuses. It is no accident, moreover, that this most recent wave of struggle was born at Columbia University–the site of the David Project’s first anti-tenure campaign and the hotspot of the anti-Zionist struggle for a generation–or that it has begun to articulate its aims in continuity with domestic struggles against the police. The campaign for boycott, divestment, and sanctions has gradually migrated outside the university with its graduates: those industrial sectors most impacted by pro-Palestine labor organizing since the start of the current genocide in Gaza—education (pre-K-12 and higher ed), healthcare, and tech—are comprised of college grads, many of whom were themselves involved in Palestine organizing.

As significant as these advances in popular sentiment have been, we should retain a sense of perspective: After nearly two decades of campaigning for divestment at campuses across the country, only a few minor holdings have divested, and the explicit political horizons of the movement have remained narrow, hemmed to the BNC’s nonviolent pressure campaign. The movement’s life beyond its campus-based origins has been confined to the sectors of the middle class that its college-educated participants left their universities to populate. Repression of the pro-Palestine student movement and its allies has only worsened. And at the level of the state, a seismic shift in popular consciousness finds politics today with a tiny minority of milquetoast liberals–the likes of which populated the U.S. Congress in scores during the 1970s–while a bipartisan Zionist coalition has pushed forward increasingly more draconian measures at all levels of government aimed at defanging the BDS Movement’s push for university divestment before it can score a single sizable win.

These measured successes bear the marks of their origin in a similarly-circumscribed political scene: campus activism, which, aside from being undercut by the routine churn of participants as classes graduate and non-tenured professors face reprisals for involvement, fosters a characteristically managerial political environment. Many of the drawbacks of the traditional “SHAC model” pressure campaign apply even more emphatically on campus. Participants exert only consumer-side leverage over their opponents; organizers understand themselves in their capacity as students and formulate their political commitments relative to visible university administrators, not even the ruling boards of trustees; political education tends to stall out at holding the university’s actions up to its supposed values as if the demonstration of a contradiction between the two is itself a victory; most importantly, a persistent gap separates a bloc of organizers who plan to merge their “student activism” with careers to come, and the organizers whose political horizons exceed their future job applications. Such a gap flows from the location of universities in the reproduction of capital and American culture: students pay (or are paid for by the institution) to invest their post-graduation labor power with specialized skills and accolades that will grant them a seat in an unstable middle-class, with one foot on either side of the capital relation. Far from pushing students to undermine their class position, this—combined with the precarious situation of the sectors of the middle class into which they’d like to enter—tends to silo them off from recognition of their impending proletarianization.

This unstable combination turns student organizing into one of many sites at which a new proletarian self-understanding might emerge as downwardly mobile university attendees stumble into confrontations with the state and capital, both anxious to shore themselves up as the present crisis deepens. But this requires de-exceptionalizing any student activist campaign, removing it from its elite trappings, and attempting to bridge campus politics with other struggles in the surrounding area, if not the world. For instance, a chant in our movement notes that police are “Israeli trained”; many involved in the struggle for Palestine point to university backlash to demands for divestment as proof that the movement winning its current demands would fundamentally destabilize the existing order, itself imagined to be ideologically Zionist. This conception is false—and frankly, whether administrators care one way or another about the state of Israel has nothing to do with the uniformity of their responses to divestment campaigns. But a movement that underscores the complicity of American civil society institutions in the genocide in Palestine pulls on a loose thread that could exhibit, if followed, the inseparability of all of our struggles.

An inventory of any given university portfolio—and a full explanation of why American police train alongside their Israeli, Chinese, or Indian counterparts—would offer student activists a cross-section of a world system in which international architectures of state repression protect a transnational capitalist class that is increasingly conscious of its short-term necessities, all of which will prove incompatible with the life of the world’s poor. To date, American labor has not risen to the May Day demands of the Palestinian General Federation of Trade Unions: an end to American manufacture and transport of weapons to Israel, reflected in trade union policy; a material campaign against companies participating in Israel’s genocide in Gaza, and a complementary campaign aimed at the United States government. The radical edges of disparate social movements and trade union campaigns have attempted to meet this practical minimum.

Last month, radical rank-and-file in the University of California schools publicly broke with the pressure-campaign political horizons of their UAW local, attempting to push beyond trade union consciousness and legally circumscribed tactics:

Rank and file union members have demanded elected UAW leadership… follow through with concrete action, and leadership has ignored this call to action. To this point, the Rank and File collective is calling for […] the collective withholding of labor in support of Palestinian liberation. We are not interested in the dictates and boundaries of the ULP strike, as we challenge its basic premises and assumptions… [W]e see it as a moment [to] begin to effect a substantial material impact against both the Zionist settler-colonial entity and the Amerikan racial capitalist-imperialist state.

Consternation from those willing to tail the social-chauvinist majority in the trade unions misses the trend embodied by this unlikely statement: the UCI radical Rank and File’s expansion of the political horizons of the Palestine movement to include confrontation with the American state is part of a broader escalation of the strategic stakes of the movement itself. Throughout the country, counter-info sites and communiques supply a growing list of autonomous actions that have materially subverted occupation, domestic or Zionist. The NYC-based organization Within Our Lifetime (WOL) has likewise begun to tie the liberation of Palestine to domestic struggles against Cop City, from Atlanta to New York and beyond. WOL has taken shape alongside Columbia’s deeply politicized and dedicated SJP chapter, which has remained a north star of the movement since proving its heroism in the Columbia occupation. In the year to come, these true leaders of the Palestine solidarity movement have the opportunity to facilitate increasingly interconnected, experimental struggles against the white supremacist ruling bloc of global capital. And those of us in Chicago and cities like it, where the movement has been demobilized and reduced to perfunctory marches and symbolic acts of speaking truth to power, must take note.

III. The View from the Lawn

Following the Al-Aqsa Flood and Israel’s immediate ground invasion and bombing campaign of Gaza, political action surged globally, as both Zionist and pro-Palestine crowds mobilized to demonstrate in streets and squares around the world. Specifically in the United States, while organizations held demonstrations in most large cities, the movement gained notable momentum on several university campuses, initially at major private universities like Harvard, NYU, and Columbia. In the months to follow, a sustained campaign of doxxing began against pro-Palestine student activists from Zionist groups like Canary Mission and the vaguely titled Accuracy in Media, tarring them as antisemites and calling for firings, as well as investigations into antisemitism on college campuses by the schools, the FBI, and the US Department of Education as violations of the Civil Rights Act; investigators began looking into Islamophobia on campuses on the same basis.

On April 17th, 2024, students at Columbia University placed about seventy tents on a campus lawn, claiming the space as a “Gaza Solidarity Encampment.” Despite being cleared quickly, the practice caught on at campuses across the country, with students at over 130 campuses creating encampments since. Currently, these have all been voluntarily dismantled or dismantled by the cops, with varying degrees of police violence at each; the photographs and videos taken of cops at Ohio State University, Indiana University, Emory, Columbia, and UCLA, to name a few, speak for themselves.

On April 25th, Chicagoland had its first encampment at Northwestern University in Evanston. Excluding one initial confrontation with the police, the camp was incredibly peaceful and inoffensive. It ended in capitulation after five days, with the university granting some symbolic victories in return for an end to what minimal nuisance the camp presented. By the time Northwestern’s encampment had ended, the University of Chicago’s had begun, and one formed at DePaul University shortly after. DePaul’s encampment lasted the longest in Chicagoland, going a little over two weeks until the Chicago Police Department raided it; we hope participants from these camps are taking similar stock of what specifically went down at each.

Organizers originally slated the University of Chicago Popular University for Gaza for the morning of May 1st on the university’s Main Quad. This relatively late date was in line with the national SJP network’s “Popular University for Gaza” campaign, which had pointed to May Day and graduation days as specific dates for calls to action when national SJP first launched it on Sunday, April 21. But given the urgency of the moment, the very announcement of this campaign became the green light for encampments and occupations, with the specifics of timing left to the judgment of local organizers. Unprepared for immediate deployment, our plans grew around the May Day launch more than a week away, as we saw each day more images of dramatic scenes coming out of the campuses that were quicker on the draw.

Our campus coalition, UChicago United for Palestine (UCUP), elaborated plans for the encampment throughout several drawn-out meetings. As an umbrella of several student activist organizations, UCUP comprises such a diverse cross-section of the conscientious part of the student body that it defies neat description. At the same time, the initiative and tempo of the coalition and its constituent groups are firmly in the hands of a relatively small number of student organizers operating in a readily identifiable way. When a clear encampment leadership body called Core eventually emerged, this small but effective cohort of political moderates would take control of representing the encampment publicly and eventually succeed in pushing their rivals away from decision-making.

This moderate bloc consisted of budding career activists and social movement managers who were “incubated” by the professionals of long-standing networks of activism-oriented NGOs, philanthropic foundations, and other liberal advocacy organizations that double as tax shelters for the ultra-rich and work assiduously to marginalize revolutionary challenges to capital and the state. It seems a large part of such “organizer training” is how to take power and hold onto it for reformist ends, even in settings that pretend to practice direct democracy. We will call this element of Core “the careerists” to distinguish them from the radicals who participated in Core, who we came to respect and admire, and who were unfortunately marginalized.

If asked to define themselves, the careerists would likely start by placing themselves in a long tradition of student activists on campus and in the wider Hyde Park area who have worked to advocate and raise awareness for unjust university practices and priorities. While this tradition certainly includes political radicals, particularly the cohort that went through the George Floyd Rebellion, the turnover rate inherent to the university keeps this tradition generally abstract beyond the immediate people one meets, with its actual upper limit being those students about to graduate when one first arrives. This lack of concrete tradition creates a sustainability problem, as the institutional depth required to maintain the organizational capacity to consistently act politically radically depends on the current cohort’s backgrounds and lives outside the group more than it would otherwise. Thus, when most of the cohort is timid or just going through the motions, it is an easy justification for external professional nonprofiteers to step in as mentors and shape them in the image of their abstract activist ideal. While the more conscious careerists may abstractly identify one way, many of their concrete traditions primarily exist off campus.

While we met individuals within the central decision-making body with intelligent and courageous analyses and proposals, the moderates outmaneuvered them in lengthy bureaucratic meetings. In response, the frustrated radicals defected from the central leadership in the ones and twos, skipping general assemblies and backing away from the camp. Others volunteered for necessary functions like kitchen work, and this division of reproductive labor removed many voices from participation in decisions. In a crucial missed opportunity, we and other radicals never formed a coherent opposition bloc or fought to marginalize the emergent inexperienced leaders disinterested in keeping the camp going.

The careerists, often as meeting facilitators, successfully framed discussions of the planned encampment around the dominant theme of “safety.” They schematized this according to three color-coded roles: Red, Yellow, and Green, which campers initially understood to mean levels of risk of arrest, with red roles facing high risk, green (entirely off-site) facing none, and yellow somewhere in between. Going over these roles took up the lion’s share of discussion in general camp-planning meetings. This dominance is partially because independent working groups coordinated plans for other practical concerns such as food, supplies, care, security, and the zero-hour deployment plan. But in hindsight, the seeds of dividing the camp with the ideology of “safety” and marginalizing those who sought to build a threatening occupation were in place from the beginning.

Nonetheless, this would have been difficult. The encampments represented an act of commoning, building shared spaces for living, thinking, and experimenting with politics together. The history of capitalist modernity is the history of commons being violently erased from the earth—including, as scholar Peter Linebaugh has argued, in the current genocide in Palestine—and replaced with societies where the bounty of the Earth and the life that populates it, have value only insofar as individual people, whose hoarding and laying waste to life is the foremost expression of their individual “right,” can buy, sell, pollute, and ultimately destroy it. Most of us trace our political awakening to moments of collective political action when the self-defeating egoism and alienation of capitalist society temporarily break down. A new sense of the possible is opened up by the bold and decisive actions taken by hitherto anonymous people, opening the possibility for new values and ways of living. In recent years, the formation of commons as a response to austerity and social crisis, no matter how fraught in practice, has revealed a deep need for community and belonging in a world hostile to it. The challenge facing those who related to the camp as an instrument to manipulate toward cynical ends lay in the powerful collective energy that emerges when masses of people experience that another world is viscerally possible.

As highly publicized occupations and confrontations unfolded across several campuses during that last week of April, the sense among us that our coalition was unduly hesitating generated some anxiety. However, the highly siloed planning process meant that the original launch date had considerable inertia behind it. It was only due to a mole that plans changed. On April 24, one week before the original launch, leaks from the main encampment Signal chat were published by the Chicago Thinker, a right-wing student newspaper. As many participants in the chat had also been using their real names, panic broke. Participants nuked the chat, and a more trusted core built a replacement and moved the launch date to Monday, April 29.

Monday. The launch of the encampment met no snarls. About two dozen of us, tents in our bags, were to mill around casually on the Main Quad and wait for the signal: campers carrying the large apartheid walls from an earlier SJP art installation in from the street. Then those of us with tents would set them up all at once, while everyone else in the vicinity would be on hand to get between the tent-builders and any interference. All of this happened according to plan and without any confrontation. Though acting quickly on a well-coordinated and instantaneous signal was certainly an advantageous move, it was likely the leak of the original launch date and our change of plans that misdirected the campus police: the Hyde Park Herald later quoted a UCPD lieutenant saying: “We weren’t expecting this until Wednesday.”

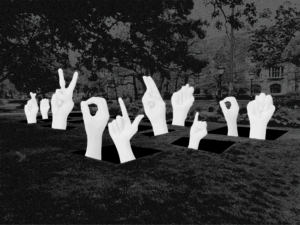

Within a few hours, the encampment expanded to cover much of the western half of the Main Quad. Most of its footprint consisted of sleeping tents, initially arranged haphazardly. The food tent was centrally located next to the central walkway, blocked off at both ends by the apartheid walls. Meetings and prayer occurred in an open space near the food tent. On the southern edge of the camp was a welcome canopy, a medic tent, various supplies tents, and an art build area. A short fence separated the camp from the central Quad walkway, soon adorned with art from collective “art builds,” where campers painted items of camp defense like perimeter barricades in a festive environment. Two autonomous zine distro tables had quickly sprung up in a central area and distributed mostly insurrectionary anarchist zines and stickers, including an impressive collection of first-hand accounts and strategic reflections on unfolding encampments across the US. Campers also set up a lending library of mostly Palestine-related books in the same area.

The presence of such unapologetic revolutionary literature in a central location caused some consternation among leaders of the encampment. It did not help that the distro-ing anarchists arrived and remained in full black bloc attire that readily marked them as radical outsiders. In the end, they dissuaded the concerned organizers from making any intervention as long as the distros were clearly labeled as “autonomous” so as not to be misapprehended as the authorized voice of the camp. They remained in their central location and were the only people distributing literature throughout the encampment, apart from the occasional wayward Spartacist or stalwart disciple of Bob Avakian. UCUP had planned several days of programming, which went ahead according to schedule. These events included guest speakers: Bill Ayers of the book Fugitive Days, local DSA Alderman Byron Sigcho-Lopez, and speakers from Jisoor, the U.S. Palestinian Community Network, and the South Shore community organization Not Me, We, alongside teach-ins, workshops, group discussions, and musical performances.

However, after several days had come and gone and the pre-planned programming had been exhausted, the opportunities for political education increasingly became spontaneous and perfunctory. Some events amounted to little more than a ritual for speakers to talk to a crowd. As for the teach-ins—whose topics ranged from Medical Apartheid in Palestine and Jewish Anti-Zionism to the 1968 DNC Protests and the Occupy Movement—only time will tell if they were effective in reaching new audiences. The ad-hoc nature of their organization, especially as time went on, was a casualty of the unsustainable system of feminized reproductive labor in the camp and contributed to a missed opportunity for a coordinated political education strategy aimed at broadening support for the movement among the curious students and community members wandering through the camp.

The general assembly proved the most available check on the careerists’ rhetoric and power. Typically held twice daily, the general assemblies presented themselves as important decision-making bodies for sundry practical matters surrounding the encampment, especially the impending threat of attack and eviction. These were the main touchstones of the collectively organized life of the camp, where we had the opportunity to voice our opinions, hear each other’s thoughts and concerns, and offer proposals regarding the encampment and its direction. They were also where the student negotiators presented their updates on the negotiation process with the UChicago administration. Facilitators invited attendees to brainstorm strategies and tactics and provoked interesting political debates.

However, these meetings were primarily facilitated by the careerists and those they trusted. Their orientation and mode of thinking were most often along the lines of liberal professional activism. Despite the appearance of deliberation, we noticed immediately that these careerists considered the assemblies to be transmission belts for decisions they had already made behind closed doors earlier in the day. When attendees took the assembly seriously and presented alternative political visions, the careerists met them with jeering hostility, shopworn privilege baiting, and whispers of “outside agitators,” “horizontalists,” and “anarchists,” which were sadly enough amplified, we learned, by purportedly supportive faculty members on the UChicago Faculty for Justice in Palestine listserv. The extent of these faculty members’ roles in limiting democracy within the encampment is a story that largely remains to be told.

The general assembly form, of course, lends itself to inaction. As challenges mounted, the careerists effectively ran out the clock each day. Nonetheless, the problem remained that they were increasingly out of step with those in the camp who took the encampment’s goals seriously, namely that we wouldn’t leave until divestment. As members of Core began to break ranks, we learned that roughly half of them never wanted the encampment. Encampments on other campuses had effectively forced them to take action lest they appear insufficiently dedicated to the cause. Once the tents went up, they immediately began plotting a dignified exit. But as the encampment wore on, an increasing mass of its rank-and-filers took this rhetoric seriously and planned to defend the camp against eviction and escalate the action toward winning its stated goals. Thus, as a powerful bloc within the encampment’s self-proclaimed leadership quietly advocated for its demise, a growing number of us made the facade of a pro-Palestine encampment into a reality.

Tuesday. The camp continued to grow, with students and community members arriving to spend time there, whether just for the day or to sleep overnight. More politicians came, and more faith leaders preached and led services. The camp remained on the western half of the quad but expanded unevenly. Rectangular pieces of plywood appeared that were enthusiastically painted and assembled into shields.

Core called a morning general assembly, asked campers to sort themselves into “high” and “low” risk roles, and then separated people into separate meetings. Core facilitators began by asking the high-risk roles on the camp’s first full day what concessions would be sufficient for them to go home. Many of us echoed different aspects of the “Disclose, Divest, Repair” demands released when the encampment first went up, indicating our unwillingness to leave without achieving at least one of these demands. In response, the student leaders said they would stay until divestment and disclosure. Many of the rank-and-file members of the encampment, ourselves included, took them at face value and echoed their willingness to fight until the end. One point of agreement between our two separated groups was that we wished to avoid at all costs the weak compromise that led the encampment at Northwestern University to self-destruct.

After this meeting, some campers moved the large walls from the middle of the walkway to a more obstructive position until they were stopped by appointed “marshals” and moderates within the leadership. At that point, they had already done the deed and moved the barriers. This pattern continued to play out throughout the encampment: a minor “escalation” (if one could even call it that, considering the kind of tactics displayed on other campuses) would occur, be stopped, then it would have already happened to enough of a degree that they could not take it back. A few careerists also wasted time condemning acts that had occurred overnight, from graffiti calling on the encampment to “Escalate for Gaza!” spray painted on buildings to the ripping down of a string of Israeli flags, which led to the individuals allegedly involved being harassed both by cops and camp marshals. There was a consistent knee-jerk response among a small cohort of self-styled leaders to throw anyone to the left of them out to dry as a gesture toward the UChicago administration that they were the “good protesters” who they could trust with a seat at the table.

Meanwhile, the camp marshals, who were technically there to keep campers safe from cops, Zionists, and other creeps, proved to be less interested in protecting the camp–as seen in their inability to stop arrests or intervene in real moments of conflict between the encampment and UCPD or Zionists–and more about mandating “acceptable” forms of protest within the camp. Their supposed authority also confused the camp: when people spotted a marshal running somewhere, people followed them, assuming support was needed, only to find the marshals concerned with scolding another unapproved “escalation.”

After nightfall on Tuesday, the large camp speakers that had played music for a dabke teach-in only moments before were switched to WKCR 89.9, Columbia University’s student radio station. The cheerful afterglow from the dabke lesson quickly subsided as we gathered around to listen to WKCR’s live reportage of the brutal police raid on the Columbia protestors occupying Hind’s Hall. The wave of student encampments began with Columbia, and as we glimpsed images on Twitter of the enormous BearCat the NYPD used to break through the hall’s second-floor windows, the bravery of the Columbia protestors was both a call to action as well as an example of the forces of the state arrayed against the encampments. Chronicling the difficulty of the UChicago encampment in answering that call—with all the attempts and fitful starts—is one of the reasons we decided to write this.

IV. Who’s Afraid of Outside Agitators?

A crucial attribute of the UChicago encampment’s tepid answer to the call of history is the lack of support or involvement from the Hyde Park/South Side community. In these early days, the encampment was established and maintained thanks to the courage and determination of many, including a plurality with no formal affiliation with the University of Chicago. The camp’s food and supplies came from a network of community members, many with no UChicago affiliation. Core put out calls for as many people as possible to travel to the camp and put their bodies on the line when the encampment was threatened by fascists or cops, regardless of their connection to the school. The crowd cheered as speakers at rallies celebrated the diversity of the encampment and the necessity of community beyond UChicago joining in the struggle. Although these organizers, in line with others across the country, professed a desire to break down the boundaries between students and community members, several incidents demonstrated their inability and unwillingness to protect non-students.

Beginning on Tuesday, UCPD arrested, detained, or otherwise harassed community members and students, as cops targeted them while they were leaving the immediate circle of the camp and picked them off, either on the perimeter of the quad or while passing through campus elsewhere. The lack of a culture of de-arrest and lingering deference to cops meant that though the organizers of the camp professed the desire to erase the boundaries between campus and community, the burden of police violence was still felt most heavily by Black community members.

Moreover, while UCUP made some overtures to activists and organizations on the South Side for their participation in the encampment, it did not unite the struggle for Palestine with their struggles once they arrived. The opposite occurred: university police harassed them, camp leaders snubbed them, participants shied away from them, and they went home with the correct impression that this movement wanted nothing to do with theirs. At this moment, a gap between the encampment as a cultural space (an exciting time to sleep on the lawn and defy administrators) and the camp as a political project (a struggle in solidarity with the world’s poor) widened.

The same myopia that prevented these student activists from making the necessary connections between the struggle in Gaza and the war at home would culminate in a fatal obsession with the unnamed, unseen, yet all-knowing and manipulative outside agitator. Used interchangeably with “anarchist,” it became a liberal synonym for “mean person who disagrees with me,” as we saw it indiscriminately applied to UChicago students and community supporters alike. With the apparent support of UChicago faculty, careerists consistently deployed this curse against those who disagreed with the careerists, including those who simply demanded democratic decision-making at the encampment. It is, of course, a dirty political trick. Since at least the anti-slavery movement of the nineteenth century, mismanagers have used the outside agitator trope to divide people fighting for liberation. During the George Floyd Rebellion, this trope formed the basis of the argument that oppressed people must be guided by some nefarious unseen hand because they lack the courage and commitment to fight back on their own. Similarly, Zionists often suggest that Iran, ISIS, and other outside agitators are secretly steering the entire Palestinian resistance rather than the courage and initiative of the Palestinian people. It was doubly offensive to find the careerists and UChicago faculty members spreading rumors about “outside agitators” running amok in the encampment, populated by dedicated activists willing to put themselves on the line for a free Palestine.

While the shameful history of the outside agitator trope is well known, the particularities of the radical scene in Hyde Park cast it in an even stranger light. Given UChicago’s relation to the South Side, both in terms of the administration’s underdevelopment of Hyde Park and Woodlawn, as well as the “radical” elements’ dependence on local organizing groups and campaigns for training and support, this characterization of community members as anarchic strangers mindlessly wreaking havoc from campus-affiliated organizers is not just ironic and misguided, but a betrayal of the very same principles ostensibly espoused by these radicals: community and solidarity.

In this context, the term “anarchist” became a flexible signifier, conveniently deployed to distance any problematic or frightening individuals from the collective life of the camp: one reportback recounts that UCUP withheld community support from a “Black Southsider who was attacked on the quad,” with marshals explaining “they’re one of the anarchists.” The activist politicking of the loudest careerist members of Core, its authors argue, stood directly in the way of the realization that Hyde Park “is a gentrified neighborhood because of this filthy campus. These rich kids and out-of-state attendees are part of the reason police so heavily penetrate the south side. Anytime UCPD harasses somebody within the boundaries of Hyde Park and the surrounding neighborhoods, it is a student’s problem.”

Past cohorts of student organizers understood this. In 2016, a student group that campaigned for the trauma center in the South Side wrote in a reportback:

Our organizing on campus has been unique because of our concrete allyship with people who are most affected by the lack of a trauma center…we have supported [the campaign] by organizing students on campus and directing as many University resources as possible to young Black organizers…

The extent to which student organizing on this campus had been successful, whether regarding the Trauma Center campaign, graduate unionization, or the occupation of UCPD’s police station lobby in 2020, was directly correlated to the degree of involvement from outsiders, here defined as people who were not university employees or students. Regardless of affiliation, these were people directly impacted by UChicago’s policies and policing who were willing to fight. Indeed, “we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality,” wrote Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. from his Birmingham cell, “tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial ‘outside agitator’ idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider.”

The parochialism of the careerists within Core extended further than the ordinary baiting of outside agitators to their very understanding of the genocide in Gaza itself. Early in the encampment, we began hearing the portmanteau “scholasticide” almost constantly. Coined in 2009 by Dr. Karma Nabulsi of Oxford University, this concept helps us make sense of the deliberate targeting of Palestinian educational institutions by Israeli forces as part of a genocidal effort to erase Palestinian culture. It can be a helpful concept when situated within the multiplicitous facets of Israeli genocide. But as the week wore on, we heard more and more about scholasticide until it seemed like this was the only thing happening in Gaza. The reason for this, we discovered, was that the careerists defined the UChicago encampment and its participants by the distinct subject position of the elite scholar. At a time when millions of people from countless backgrounds and occupations were coming together all over the world in powerful mass demonstrations against Israel, they framed the whole encampment as a matter of elite academics taking action on behalf of academics. Instead of allowing the university to be a site of more generalized struggle, they upheld the social division of labor and focused on their career paths.

It is not an exaggeration to say that some careerists hung the entire occupation on the concept of scholasticide. As negotiations stalled and general assemblies became increasingly contentious around questions of tactical escalation, one prominent careerist argued that the strategic horizon of the camp should be as follows: Negotiators should insist that the university “acknowledge the scholasticide in Gaza.” If the university does not budge, Core should prepare to cooperate in the camp’s eviction by the police. The outcome of the camp, this organizer argued, would be a victory: the “media narrative” in which the “UChicago administration refused to acknowledge a scholasticide.” When asked what media outlet he thought would care enough about this issue to frame it this way, besides the UChicago student newspaper, the organizer grew quiet. To make matters worse, this was a sidebar conversation when this same organizer publicly avowed that the encampment would stay until divestment. And even if he had succeeded in the plan to throw the whole camp away on the “media narrative” of “scholasticide,” nobody knows what that word means anyway.

“Modern capitalism’s spectacularization of reification,” wrote the Situationist International, “allots everyone a specific role within a general passivity. The student is no exception to this rule. [Theirs] is a provisional role, a rehearsal for his ultimate role as a conservative element in the functioning of the commodity system. Being a student is a form of initiation.” Any serious challenge to the society the university thrives in must begin by rejecting the particular identity of the university student or worker confined to the parochial concerns of the ivory tower and removed from the world’s toil. By forcing the definition of the camp within such narrow parameters, the careerists sought to fix the definition of the camp in the same terms as the capitalist managers of our society do: keeping struggles siloed off from each other and keeping their participants under expert control. An effective movement must consider the university, or wherever else struggle kicks off, to play no privileged role in the global movement, especially with regards to its specialized status within the capitalist division of labor, and to be instead the accidental location from which people can launch a much more generalized struggle, breaking down all walls that divide us in the process. In short, so-called academics must abolish themselves.

V. Core and Periphery

Wednesday. With Columbia’s tear gas and broken windows fresh on our minds, the murmurs of defense and autonomy grew more strident. In addition to the raid of Hind’s Hall, videos of the attack on the UCLA encampment by Zionists aiding the police and the attempted raid on Cal Poly Humboldt demonstrated the threats encampments faced. The threat of police violence became even more pressing when the Dean of Students, Michele Rasmussen, threatened the encampment representatives with a police raid: UCUP had denied responsibility for the graffiti, so this was evidence that “outsiders” had entered the camp, allowing the university administration to claim “safety concerns” as an excuse for dismantling the encampment altogether. Ironically, the penchant of the careerists to red-bait their political opponents in the name of safety was putting us all in danger. In response, student negotiators demanded amnesty for the negotiating representatives, postponement of a police raid on the camp, and a direct meeting with the President and Provost with spectators and a faculty advisor.

However, the rank-and-file’s idea of defense was far more active than the conciliatory horizons advocated by these negotiators. Community members had erected more fences and barricades through Tuesday night and Wednesday morning. Unfortunately, moderate busybodies moved them back or uprooted them by noon. Amongst that day’s official camp schedule of teach-ins and rallies, two shield trainings happened directly under the noses of these careerists. Those involved with coordinating them did so beautifully; someone simply slid up to a hot mic, asked to speak, and told people a “crowd safety” training would be happening, at which people practiced defense drills, formations, and maneuvers with these mobile barricades.

The shields, mostly particle boards colorfully decorated during the previous day’s art builds, would become a significant point of contention between the camp’s rank-and-file and the careerists over what it meant to take seriously the oft-chanted mantra “We keep us safe.” Indeed, the controversy they would generate contains the dynamics of the entire encampment in miniature. Many comrades, particularly those with experience in parts of the US that have seen violent fascist street activity since at least 2016, considered it completely obvious that we would prepare shields and conduct training for using them in formation. Meanwhile, self-identified camp leaders and faculty members, with no street experience besides glorified parades, were openly hostile to the shields and training throughout the week. We understood this dynamic as a token of the uneven dissolution of civil society in the United States. Many Hyde Park intellectuals who speak truth to power from the comfort of the most heavily policed neighborhood in the US, where most fascists are (hilariously enough) afraid to go, mocked the notion that self-defense amounted to anything more than linking hands and presenting your bare forehead to your would-be attacker. Many of us have lived in or traveled to places where vigilantes brutalize and murder leftists: the careerist and faculty denigration of basic self-defense was a delusion born of extreme privilege.

Though everyone at the encampment saw the same brutal acts demonstrated against other encampments and occupations across the country, particularly at Columbia and UCLA, our reactions were sharply divergent. While the rank-and-file’s drive to actively defend the camp against the university grew in response to these events, the careerists in Core, formerly content to ride the encampment’s popular momentum until it died out, grew increasingly fearful of violent repression and, in turn, popular politics against that repression, which they didn’t quite know how to wrangle. Their browbeating and crowding out of radical elements in UCUP had paid off, and these careerists were now the faces of the movement at UChicago. However, it was increasingly likely that this movement would be associated with open and active hostility to the university and its response, extreme brutality. If the careerists were previously content with going home when things died down, it was precisely then that they began to constitute an active tendency that wanted to dismantle the camp: we refer to this tendency as the Surrender Faction.

After Tuesday’s conflict over the slight movement of the few barricades present, more tents pushed the camp’s boundary further northward. Light barriers and mesh fencing were erected around the North, East, and South sides of the camp in response to incursions by people determined to harass participants, including a right-wing streamer, constantly followed by campers waving flags and keffiyehs in his face, along with fascist frat boys, unhinged Zionists, and other obsessed sickos. Though campers held several “de-escalation” training sessions, hostile actors were previously able to walk through the camp because any kind of barrier was initially deemed an “escalation” and thus out of the question.

Wednesday was May 1st, and a May Day march elsewhere in the city had pulled many people away from the camp for the day. At general assemblies, the push for alternatives to Core gained steam, as campers advocated for working groups and a spokescouncil system to replace the shadowy decisions Core announced twice daily. By this time, a popular term circulating throughout the camp and the social media sphere around the encampment movement was the imperative to pursue “escalation.” Unfortunately, this remained hazily defined, and even when concrete proposals were floated, such as the occupation of one of the encampment’s adjoining buildings, the case was never compellingly made for why we should undertake these tactics, or how they would move the dial forward in the struggle, besides the tautology that they would be an “escalation” and that would be good.

This is a self-critique as much as anything; we believed that the logical next step was to take a building, and we advocated this position. But why? To what end? The most vocal proponents of this plan simply pointed out that it was happening elsewhere. As people in favor of a revolution in the United States, we understand that deepening tactical militancy can be a good thing, especially as it helps cohere new associations of comrades who build trust while building comfort with risk and breaking the law. We could have made this argument plain and won some people over. But the imperative to escalate remained ill-defined, almost an article of faith. What was missing was a coherent and communicable politics behind all the escalatory posturing. In the end, the very idea of “escalation” even ended up being appropriated to mean doing nothing.

Thursday. In the morning general assembly, Surrender Factionists presented a plan for ending the encampment. Despite the bluster in the speeches that a handful never tired of subjecting us to, they just wanted to go home. They proposed to host a final Friday rally before disbanding and framed this as a “strategic retreat.” They also presented the Gaza Scholars at Risk program offered by the university administration: UChicago would offer temporary university status to a handful of Palestinian scholars to help them escape the genocide. Though they had not yet discussed or released full details to the general camp, the Surrender Faction framed it as a win. For our part, we considered it a hostage situation in which the administration made the lives of Palestinians and their families conditional on the camp’s good behavior. Meanwhile, in the face of demands for “escalation” from the rank-and-file, some Surrender Faction organizers ostensibly agreed, then liberalized the demands by arguing that “being here is an escalation.” They added that what the university offered was good enough to settle.

Thursday was also the first day the camp negotiators, led by two members of Core, met with President Alivisatos and Provost Baicker. Though the student negotiators declared to the President and Provost they could not make final decisions for the camp and would have to bring any proposals back to the final assembly, the exact details of the negotiations remained secret. The meeting minutes would not be released publicly until the encampment had ended. At general assemblies, Core organizers shared highlights and selections of their meetings with the administration; despite requests to create a negotiation working group to involve the whole camp, none materialized. Thursday also marked the concrete appearance of the Surrender Faction, with an anonymous student negotiator stating, “I don’t want this encampment to go on much longer because what we have seen across the country is scary and disturbing to me.” While this was happening, members of the encampment wanted to do more than just sit around in our tents. That Thursday afternoon, as the pigs tried to take down two Palestinian flags hung up on trees across from the camp, we surrounded their ladders and chanted. Outnumbered and shaking, they only managed to take one flag down before they fled. While this was happening, other campers noticed the large flagpole in front of Levi Hall was empty. A Palestinian flag was quickly attached to the line, flown up, and its line thoroughly taped onto the pole. Protestors protected the flagpole from cops and administrators with bodies and barricades for an hour in the rain until efforts to take it down abated.

Rain continued throughout the day, and Core continuously pushed back the second general assembly. It was not until nearly midnight when we saw Core organizers hurrying under the rain towards the outdoor cloisters between Swift Hall and Bond Chapel that the campers realized that this was the awaited general assembly, where Core would make decisions without their participation. We swarmed in, depriving them of their secrecy. At this meeting, it became clear that the negotiators and the careerists were working closely with the Coalition for Justice in Palestine (CJP)—ironically enough, an outside organization whose involvement and direction in negotiations UCUP had not disclosed to the camp. We also learned negotiations had already occurred and that UCUP had accepted certain conditions on behalf of the camp without any camp-wide involvement or discussion. Citing the rain, which the enclosure sheltered us from, as the cause for curtailing any deliberation, facilitators rushed through announcements and refused to talk about escalation. Instead, they introduced a CJP member, who addressed the small crowd, attempting to convince us to accept CJP leadership.

While we had been told the meeting would not include deliberation due to time constraints imposed by the weather, CJP’s professional organizer filibustered at great length, touting his organization’s immense resources and influence. He aggrandized the group’s weekly marches in the Loop, which had been steadily declining in participation since October, with no plan for moving beyond this stale form. And he promised that, if placed under CJP control, the encampment would receive a massive infusion of resources and bodies in the coming days.

As he spoke, sighs and murmurs echoed throughout the assembled crowd. A quartet of women in hijabs shook their heads and whispered among themselves; it was not their first run-in with this organizer, and they were not impressed. Multiple attendees, who had braved the miserable weather to have a discussion, spoke out against the lack of transparency on display and the shameless attempts of the Surrender Faction, who had been fighting democracy within the general assembly since day one, to pass off the camp to a third party, since they were themselves clearly out of momentum. If the power should belong to the people, why is it so difficult for some organizers to relinquish control? Tired and wanting to go home, these organizers preferred to install a new sovereign rather than let the camp govern itself. This decision was unpopular, but they successfully maneuvered to end the meeting, taking advantage of everyone’s tiredness from listening to the CJP organizer’s rant as midnight approached. We left with enhanced division and discontent, high tensions, and no sense of the way forward for the camp.

It is worth reflecting on the sad fact that the careerists and CJP found so many people in the encampment willing to take their proclamations as commands and to help them resist calls for democratizing decision-making. A lack of collective political experience pervading US society has produced a kind of activist who relates to political movements as some combination of consumer and low-level employee, following the directives of whoever represents themselves as in charge, especially if they can pass themselves off as the representative delegate of an oppressed group of people. Despite noble efforts by individuals and crews who were low on pre-existing political connections and were eventually badjacketed for their troubles, no militant and serious opposition bloc appeared capable of reversing the performative, reformist strategic horizon set by the careerists.

We have since concluded that we erred by assuming all of Core was a monolithic bloc that handed down agreed-upon diktats to the mass of participants. We would later learn that Core was, in fact, so internally divided that its meetings primarily served to wear down and alienate its radical bloc, who then avoided the charade of the general assemblies. Identifying and building ties with these more radical organizers could have completely altered the face of the encampment, especially given we ascribe no profound social or political intelligence, or even charisma, to the careerists who kept control of the camp. Instead, their success demonstrated a low level of political literacy among the camp’s rank-and-file, who most often simply did what Core said; a lack of organization among radical participants; our self-marginalized inability to consider that we had more potential allies than we realized; and, above all, the insufficiency of all radical participants to build an alternative bloc and political vision with which we might have contested leadership of the camp.

Even if Core was more amenable to radical proposals, the very nature of the group as an informal, invite-only shadow council would curtail its attempts at creating effective decision-making processes. Even though such a structure could successfully delegate tasks during the planning stages, its overworked personnel could not manage and defend the 24/7 on-the-ground logistical operation that is an encampment when secrecy and security were paramount. Between drawn-out difficult meetings where emotions ran high and fearful sleepless nights spent waiting for fascist violence, the organizers failed to see that the much larger community that had gathered around them had a direct interest in the perpetuation of the camp and the skills to accomplish that task in a democratic and accountable manner, without extraneous layers of “leadership.”

On the other hand, the proposed models to “decentralize” decision-making failed to escape their birth conditions. As discussed above, radicals designed effectively the decentralized organizational models of the 1990s to separate tactical deliberation from any discussion of the movement’s disparate strategic horizons. In our case, the creation of a variety of working groups separated radicals, further preventing us from altering the camp’s trajectory with surgical precision: careerists sidelined disputes over their conservative vision for the camp or at least confined them to communities of like-minded but provincial militants, such as the Popular University’s “camp defense” working group. Thus, the careerists were left to shape the broader identity and aims of the camp. Ultimately, the same problems of the camp’s “periphery” bedeviled its “core,” but with fewer avenues to resolve them since one tendency within UCUP could at least make the camp in its image.

Working groups and spokes-councils, which we helped popularize, allowed militants to find each other and laid the foundations for relationships that would outlive the camp. However, movements should be judged at a minimum by whether they achieve their ends, and the “decentralizing” organizational models proposed by well-meaning radicals in the camp brought us no closer to changing the trajectory of the encampment. Rather than well-meaning gestures at democracy, which assume that those deliberating share a shared strategic intelligence and political will, only rarely glimpsed at the encampment, it may benefit movement radicals to build their own broader constituencies of like-minded and skilled militants who can intervene at opportune moments, connected to extant organizations but not beholden to the in-the-moment conservatism of full-time activists. At the outset of further long-term actions, we should also remember that an established organization is difficult to meaningfully alter and push against formalizing what initial secrecy measures may prove necessary to get any substantial action off the ground. Abolish Core!